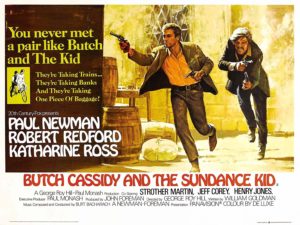

50 Years of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

A west in transition is one of the main themes of George Roy Hill’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid which celebrates the 50th anniversary of its theatrical release in October 2019. The iconic western starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford – and scripted by Oscar-winner William Goldman – sets the tone in its opening scene. Surveying a modern-day bank in late-1890s Wyoming, Butch (Newman) enquires as to why there are so many security measures in place as opposed to the former establishment which he most likely has raided in former times. The response he receives is that the old bank kept on getting robbed. ‘Small price to pay for beauty’ Butch retorts as he departs the premises. The notion of a world in change and individuals who are no longer adept at moving with the times is one which the 1969 film re-visits on several occasions during the course of its narrative. It was a theme which was reflected in another seminal western of the same year, namely Sam Peckinpah’s masterpiece The Wild Bunch. Like the sometimes disparate gang in that latter film, the two protagonists here are men who have dared to run contrary to the tenets of modern civilisation for far too long. They have no place in this new world and have become something of an anachronism in the process. At an early point in the film, the essentially affable Butch (‘Boy, I got vision and the rest of the world wears bi-focals’) is challenged to a duel by a member of his own gang. He survives on that particular occasion, but there is a sense of foreshadowing which the story persists with. The west as the two men once knew it is changing fast and the outlaws’ days are duly numbered.

One of the most notable features of the story is that Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is – for the most part – a pursuit film. Having raided the Union Pacific Overland Flyer train on two occasions too many, the outlaw heroes find themselves tracked relentlessly by a super-posse in the employ of one E.H. Harriman. Butch and the Kid run and run, but their pursuers are live to their tricks and attempts at evasion (‘Who are those guys?’). Eventually, they decide to flee to South America (Bolivia to be precise) at Butch’s suggestion. When William Goldman shopped his original script around the studios in the latter half of the 1960s, he was greeted by many a po-faced executive who balked at the idea of the heroes fleeing to another country. When the screenwriter pointed out that this was, in point of fact, a historical accuracy, the response of one of the powers-that-be was quite memorable – ‘I don’t give a shit. All I know is John Wayne don’t run away.’

One of the film’s more pivotal scenes occurs when Butch and the Kid prevail upon their friend and lawman Sheriff Bledsoe (Jeff Corey) to aid and abet them in their efforts to elude the super-posse. Agreeing to be tied up by the two men, and providing false information to their pursuers, Bledsoe delivers a pointed warning about the men’s future, or lack thereof to be more precise – ‘You should have let yourself get killed a long time ago when you had the chance. You may be the biggest thing that ever hit this area, but you’re still two-bit outlaws. I never met a soul more affable than you Butch, or faster that the Kid, but you’re still nothing but two-bit outlaws on the dodge. It’s over, don’t you get that? Your times is over and you’re going to die bloody and all you can do is choose where.’

The pairing of Newman – the already-established movie star – and Redford – the hottest newcomer on the block – was a stroke of genius in hindsight, but actors such as Steve McQueen and Warren Beatty were apparently considered before the Sundance Film Festival founder took on the part. The onscreen chemistry between himself and Paul Newman is one of several reasons why the film endures so well to this day and the constant quips which Goldman’s script provides them with adds to and informs its bittersweet tone. The famous cliff jump scene (in which Sundance reveals the fact that he can’t swim) is one such instance, as is their arrival in a desolate location in Bolivia (‘He’ll feel better after he’s robbed a couple of banks’). But credit also to the other cast members, in particular The Graduate’s Katharine Ross who plays Etta Place (the duo’s companion who accompanied them to Bolivia). The nature of Etta’s physical relationship with the Kid is never in doubt, but far more interesting is the nature of her affection for Butch and the obvious love he holds for her (‘Butch, do you ever think if I’d met you first, we’d be the ones to get involved?’). When she agrees to travel with the two to Bolivia, Etta also hints at the pair’s eventual fate when she tells them quite pointedly that she won’t watch them die – ‘I’ll miss that scene if you don’t mind.’

In penning his original screenplay about the famous outlaws, William Goldman clearly adheres to the maxim articulated by the newspaper editor in John Ford’s 1962 The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance – ‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.’ This is also the case with respect to the Bolivia section of the film. Upon their arrival in the landlocked South American country, the three companions are initially disappointed with their new surroundings, but gradually they learn to adapt. Some of the film’s more humorous moments occur as Butch and the Kid try to get by in their outlaw trade with a rudimentary smattering of Spanish (‘specialised vocabulary’ as Etta refers to it). Their efforts are entirely inept, but Goldman’s script pokes fun at this in a sympathetic way. The pair are so likable that we, the audience, indulge their every whim and failing. Known locally as Bandidos Yanquis, the two men are reminded of the outstretched arm of law and order when a familiar figure (in the guise of Joe Lefors) arrives to apparently continue his pursuit of them. Taking on the part of payroll guards, the pair attempt to go straight for a time, but fate and their fidelity to a past means of existence overtakes them one more time. Sensing the pair’s intractability in this latter regard, Etta decides to head home by herself. It’s not so much an abandonment as it is a feeling of resignation – ‘I might go home ahead of you’ she tells Sundance in such a vein. She realises only too well the hail of bullets that inevitably awaits her beloved men. This is not a scene which she will witness. Neither will we the audience as it so happens.

Etta’s decision to return stateside by herself is of course the beginning of the end of the story and the film and it does not require me to set the scene for the climactic shootout which occurs between the two men and the forces of law in the square of a small Bolivian town. The freeze frame (as pictured above) which Hill chooses to employ at the end is another example of fact being supplanted by legend. The set-up in Goldman’s script does not actually represent the truth of Cassidy and Sundance’s ultimate demise, but it does make for far better storytelling as well as heroic prowess. Who would want to see either of these two largely lovable characters succumb in a bloody heap? Not Etta as depicted in the film. Not the audience either. The still image at the film’s end represents the precedence that cinematic narrative takes over actual history in this respect. To the naked eye, these men never die; they are forever; everlasting. Passing into the annals of folklore and legend.

Ranked as the 7th greatest western of all time in the American Film Institute’s Top 10 list of 2008 (Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch is one place above it), Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid remains one of the very best (and certainly one of the most charming) of the genre as a whole and its sheer entertainment value remains undiminished some 50 years after its initial release. There are so many elements of the film which work well (including Burt Bacharach’s jaunty score and the burnished cinematography of Conrad Hall), but principal kudos must extend to the inventive script by Goldman, the excellent direction of Hill and the peerless pairing of Newman and Redford. The winner of four Academy Awards (Best Original Screenplay, Best Cinematography, Best Original Score and Best Song), Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid deserves its place as one of the best westerns ever made, as well as one of the greatest buddy movies. Some four years after its release, Hill, Newman and Redford teamed up again for 1973’s The Sting to great effect. The latter won seven Oscars subsequently and enjoyed a huge box office haul for its day. The reuniting of Newman and Redford on the silver screen surely had much to do with that I would suggest; so too did the considerable success of their previous film together. On that note, happy 50th birthday Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. We’re truly grateful that these two memorable cinematic characters will go on living forever.