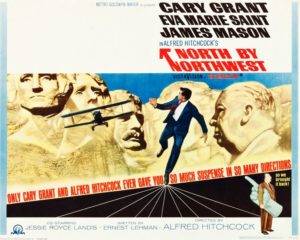

60 Years of Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest

Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest celebrates the 60th anniversary of its theatrical release and we look back upon this iconic thriller starring Cary Grant which has entertained countless numbers of cinema fans over the last six decades. Described as ‘a fantasy of the absurd’ by its famed director, North by Northwest is first and foremost an elaborate chase movie in which a debonair advertising executive by the name of Roger Thornhill (Grant of course) becomes a victim of exaggerated circumstance following a case of mistaken identity. The theme of the innocent man accused in the wrong was one which Hitchcock returned to many times during the course of his prodigious career – need I mention examples such as 1935’s The 39 Steps, 1942’s Saboteur or 1956’s The Wrong Man? The territory of North by Northwest may seem familiar in this respect, but the genesis of the project was unconventional to say the least. Working for MGM on an adaptation of the novel The Wreck of the Mary Deare, Hitchcock and screenwriter Ernest Lehman had hit the proverbial wall in terms of writer’s block. Searching for a justifiable reason to continue their professional engagement, the director shared his desire to film a chase scene atop South Dakota’s Mount Rushmore National Memorial. Lehman duly took the bait and set about conceiving the ‘Hitchcock picture to end all Hitchcock pictures.’ Much brainstorming later, the two men had fabricated a meandering plot which also involved the U.N. Headquarters and the 20th Century Limited train. For good measure, a soon-to-be famous crop-dusting scene was also thrown in, but more about this in due course.

Life is blissfully dull for Grant’s Roger Thornhill when we first encounter him. The Madison Avenue man is middle-aged (Grant was in his mid-50s at the time) with, in his own words, ‘a job, a secretary, a mother, two ex-wives and several bartenders that depend upon me.’ He’s a man who appears to be master of his domain at the beginning of the film, but this status quo of his is dramatically altered when two thugs pick him up and forcibly escort him to a Long Island estate. Thornhill meets Phillip Vandamm (a similarly suave but forbidding James Mason) who insists on addressing him as George Kaplan. When Thornhill refuses to play along with this apparent game of cat-and-mouse, Vandamm instructs his henchmen (including Martin Landau’s Leonard) to see that he meets with a timely accident. One of the remarkable things about the scene in which Thornhill is forced to drink a bottle of bourbon is the essential aura of civility which surrounds the scene; it’s staged in a well-appointed library with ambient lighting. Vandamm’s right-hand man – as played by Landau – first pours the bourbon into a glass before pushing it on the physically-restrained Thornhill. This juxtaposition between gentility and peril is a prominent feature of North by Northwest – even the baddies (most especially Mason and Landau) are purportedly men of manners and culture.

Hitchcock maintained that ‘drama is life with all the dull bits cut out’ and North by Northwest most certainly adheres to this maxim and then some. There are so many different strains to the film – including suspense, comedy, drama, action and romance – that an article of this nature and length cannot do justice to them all, but suffice it to say that Hitchcock and Lehman delivered a first-class entertainment which improves with repeated viewing. L.A. Confidential director Curtis Hanson summed it up extremely well when he remarked that the film ‘still plays so well even though so many of its elements, that were new at the time in 1959, have been so replicated and imitated.’ There is a popular school of thought which even suggests that this was a forerunner for James Bond, who made his first screen appearance a mere three years later in 1962’s Dr. No. I don’t quite buy into this theory myself, but there are definite parallels to be discerned if one is of such a view. Word even has it that the aforementioned crop-dusting scene inspired a helicopter sequence in 1963’s From Russia with Love.

Having survived his initial brush with Vandamm’s men (with nothing more than a drunk-driving charge and a sore head), Thornhill attempts to convince the authorities and his own mother (Jessie Royce Landis) that his life is at risk. The famous elevator scene (as pictured above) in which Landis’s character politely enquires as to whether the heavies are really trying to kill her son is an absolute hoot, but it’s also a fine example of how mood shifts quite abruptly throughout the course of the film – tension, laughter, action, danger and so on. The U.N. General Assembly Building scene (one of the locations on Hitch’s wish list) is the point at which the chase element of the film begins proper. Seeking out the alleged owner of the Long Island home in which he was deliberately intoxicated (a man by the name of Lester Townsend (Philip Ober)), Thornhill is framed for his murder and flees the complex a wanted criminal; there’s even a photographer on the spot to capture his guilt-ridden image for the papers (no need for the limitless wonders of social media back then). At the very height of his film-making powers at this time (North by Northwest is sandwiched in his oeuvre between 1958’s Vertigo and 1960’s Psycho), Hitchcock had a mastery of the medium like few others and understood how certain dollops of exposition for the audience (but not the central character at this point) served to heighten the sense of dramatic tension. This is the reason why we have the seemingly banal conference scene following Townsend’s murder. An older gentleman, known simply as The Professor (Hitchcock regular Leo G. Carroll), briefs his fellow government agents as to the extraordinary fate which has befallen Thornhill. We even learn that the so-called operative George Kaplan is a fictitious character, devised primarily to distract Vandamm from the presence of a bona fide spy. The meeting ends in a state of irresolution with some members of the government agency in favour of assisting the hapless Thornhill and others content to leave him to chance – ‘Goodbye Mr. Thornhill, wherever you are.’

We come now to one of the most famous sequences in North by Northwest which involves Thornhill sneaking onto the 20th Century Limited train, bound for Chicago, and encountering Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint) for the first time. Hitchcock films were well-known for their sense of play and allusions apropos gender relations and the scene in which Thornhill and Kendall exchange pleasantries to this effect (euphemistic language on my part) is one of the very best the director has ever devised. Kendall has it arranged that Thornhill (whom she recognises) will be seated at her table in the dining car and the conversation which ensues between them is laden with sexual innuendo. A wonderful example of this runs as follows:

Kendall: ‘It’s going to be a long night.’

Thornhill: ‘True.’

Kendall: ‘And I don’t particularly like the book I’ve started.’

Thornhill: ‘Ah.’

Kendall: ‘You know what I mean?’

Thornhill: ‘Ah, let me think. ‘Yes, I know exactly what you mean.’

It goes on in this manner and I think you know exactly what I mean as well. Hitchcock rarely ceded any power or authority on his film set, but there was one piece of dialogue which the powers-that-be felt cut too close to the bone as regards the sexual act and the director was persuaded to change it. When Kendall reveals to Thornhill the fact that she had tipped the steward five dollars so that he would be seated at her table, the latter asks (as one might do) if this is a proposition. The response on Kendall’s part – ‘I never make love on an empty stomach’ – was duly amended to the somewhat less suggestive ‘I never discuss love on an empty stomach.’ On this occasion at least, the prudes got their way ever so slightly.

The scene which follows in Kendall’s compartment on the train has been correctly labelled one of the sexiest scenes in all of cinema without the sexual act. Thornhill and Kendall become better acquainted (there’s yet another euphemism on my part) and this leads to some more titillating language on a par with the dining room scene:

Kendall: ‘How do I know you aren’t a murderer?’

Thornhill: ‘You don’t.’

Kendall: ‘Maybe you’re planning to murder me right here tonight.’

Thornhill: ‘Shall I?’

Kendall: ‘Please do.’

It’s notable, however, how this scene concludes as a close-up of Kendall embracing Thornhill suggests for the first time that she may have ulterior motives. Hitchcock the storyteller believed fervently in the power of image above language and this particular shot emphasises the effectiveness of this approach. Sure enough – just a short time later – and again through the power of image – we the audience learn that she appears to be in league with none other than Phillip Vandamm.

Upon their arrival in Chicago, Kendall informs Thornhill that she has arranged a meeting for him with the real George Kaplan (a make-believe character as has been established) and our sense of concern for his welfare returns once more with a vengeance – again the alternations in mood which work so well throughout the film. The lead-up to the famous crop-dusting scene is examined by a couple of contemporary film-makers in the documentary Destination Hitchcock: The Making of North by Northwest and all are agreed that it is a model in the art form of cinema with regard to the tension and palpable feeling of danger which Hitchcock manages to create. The premise of the situation is quite ridiculous as Curtis Hanson has quite rightly observed – ‘Why would the villains lure Cary Grant to the middle of nowhere in order to shoot him from an airplane? And yet it feels right.’ It’s akin to a few of the more ludicrous ways by which some of the baddies have tried to rid themselves of one James Bond over the years, but it’s also entirely in keeping with Hitchcock’s modus operandi for the film – ‘a fantasy of the absurd.’ More to the visual point perhaps was the director’s innate desire to film a truly unique pursuit sequence which was bereft of the conventional darkened streets and narrow alleyways. And boy does it ever work in this respect. It fully conformed to the director’s wish that the vista in which he shot the scene (on Garces Highway, East Bakersfield, California) be nothing more than ‘just bright sunshine and a blank, open countryside with barely a house or tree in which any lurking menaces could hide.’ Director Guillermo del Toro makes an interesting observation about the scene also when he suggests that ‘You don’t question the logic because the motion and the emotion carries you through. Reality is boring, reality you get every day.’ This returns us to the previous remark of the master himself when he observed that ‘drama is life with all the dull bits cut out.’ The crop-dusting scene certainly adheres to that principle and then some. Incidentally, the close-ups of Grant falling to the ground as the plane flies over him were realised on an MGM soundstage with the plane footage projected behind him. Grant was much too big a star to risk otherwise.

The art auction scene in which Thornhill confronts Kendall, Vandamm and Leonard is one of my own personal favourite exchanges from the film and also serves to confirm what a perfect cast Hitchcock had managed to assemble. Mason’s character has made a snide remark about Thornhill’s performance as the supposed innocent man on more than one occasion before, but the lines he delivers in this particular scene are especially derogatory and delivered by a truly wonderful actor in his element – ‘Has anyone ever told you that you overplay your various roles rather severely Mr. Kaplan?’ And then a short time later – ‘It seems to me that you fellows could stand a little less training from the F.B.I. and a little more from the Actor’s Studio.’ The upshot of all this barbing is that Thornhill survives yet another attempt on his life and is picked up by the police when he deliberately disrupts the serious bidding which is at hand.

A key turning point in the film generally – and for Grant’s character most especially – arrives when The Professor (Leo G. Carroll as pictured above with Grant) reveals the true role of Eve Kendall with respect to Vandamm – she is the real government agent for whom the fictitious George Kaplan has been invented in order to distract the sinister spy. Thornhill’s reaction to this piece of information marks an important juncture for him in the story. No longer the victim of extraordinary circumstance, he becomes a man of responsibility imbued with a fresh sense of purpose. Contemporary film-makers such as Hanson and del Toro note how this moment marks a decisive transition for the character. Up to this point he has played the archetypal middle-aged playboy without any concrete concerns to trouble him. A hollow man is the phrase which is employed by one of the film-makers in the aforementioned documentary Destination Hitchcock: The Making of North by Northwest; even the O in his name stands for nothing as he has freely acknowledged to Kendall. Thornhill becomes the protagonist of the piece at this moment and remains so for the rest of the film. His actions from this point on speak volumes in this respect. Consider, if you will, his decision to go along with his own faked shooting at the hands of Kendall at the Mount Rushmore visitor centre. The ploy – as evidently suggested by The Professor – is carried out to take the heat off Kendall who is now the subject of some suspicion on Vandamm’s part. Meeting a short time later in the woods (the scene in question would you believe was shot in the studio), the contrite Thornhill learns to his consternation that Kendall must see her mission through to the very end – she must depart the country with Vandamm on a plane and seek to prevent him selling whatever classified information he has managed to procure.

Thornhill is subdued by The Professor’s driver and locked in a hospital room to prevent him from interfering with the plan. He escapes naturally and makes his way to Vandamm’s house to rescue Kendall – was my previous remark about him becoming the protagonist not well made? The new man of courage overhears a key conversation which occurs between Leonard and his boss in which the former airs his opinion that Eve is working for the other side – ‘Call it my woman’s intuition, if you will, but I’ve never trusted neatness. Neatness is always the result of deliberate planning.’ Producing the same pistol which Kendall had used to shoot Thornhill, Leonard demonstrates to Vandamm how the apparent shooting at the visitor centre was nothing more than an elaborate sham. Incensed and somewhat red-faced at this disclosure, Vandamm determines to deal with the problem in his own personal way – ‘Like our friends, I too believe in neatness Leonard. This matter is best disposed of from a great height…over water.’ I don’t propose to repeat the intricacies of the plot as it unfolds for the next few minutes of the film (watch the whole thing again, as you ought to), but suffice it to say that Thornhill escapes the house with Kendall in tow. The two are pursued by Vandamm and his men to the top of Mount Rushmore where they are forced to partially descend the iconic sculpture. Now recall if you will the fact that this chase scene served as the genesis for the film. Hitchcock and Lehman effectively began with an ending (as it subsequently transpired in the story) and worked up the other elements and narrative strands of the film from this premise. On a purely personal level, I have to say that I’m happy the great director didn’t run with one of his original ideas which was to have Cary Grant hiding in Abraham Lincoln’s nose before an ill-timed sneeze gives him away to his pursuers.

The climactic scene on the face of Mount Rushmore (roughly between the heads of Washington and Jefferson) is unquestionably one of the greatest movie finales and was in keeping with Hitchcock’s predilection for shooting key sequences at world-famous locations and structures – consider, in this latter regard, his use of the London Palladium in The 39 Steps (1935), the 1939 New York World’s Fair in Mr. & Mrs. Smith (1941), the Rockefeller Center, Radio City Music Hall and Statue of Liberty in Saboteur (1942) and the Golden Gate Bridge in Vertigo (1958). And that’s leaving out mention of other films such as Strangers on a Train (1951) and To Catch a Thief (1955) which employ extensive use of well-known urban and exotic locations. For the benefit of the article at hand, it’s worth noting the fact that the close-up shots of Mount Rushmore were completed on a soundstage at MGM over a five-day-period. For one thing, the prominent sculpture in South Dakota is a National Memorial and filming of this nature would not have been permitted; it goes without saying also that the tumbles and falls involved would have been much too dangerous for Grant and Saint to perform on the real Mount Rushmore (although the Oscar-winning actress does relate picking up a slight cut for her troubles; the moment in question made it into the final cut of the film). Following on from the melancholy and weighty psychology at play in 1958’s Vertigo, Hitchcock said that he wanted to do something generally free of the symbolism permeating his other films. North by Northwest pretty much complies with this intent for the most part if you blissfully overlook the final scene in which the train (with Thornhill and the new Mrs. Thornhill among its passengers) enters a tunnel. Acknowledged by the director as a ‘phallic symbol’ the shot was described by him as ‘probably one of the most impudent shots I ever made.’ Needless to say, we are inclined to forgive him this one slip as regards charged symbolism – the film’s ending is a playful stroke which is most certainly not out of keeping with the exhilarating tone struck throughout.

It’s a testament to Hitchcock that four of his films were listed by the American Film Institute (AFI) as the very best in the genre of mystery when it unveiled its Top 10 selections in 2008. Vertigo occupies the number one spot and Rear Window is there at number 3; North by Northwest ranks at number 7 and Dial M for Murder comes in two places behind it at number 9. On the review-aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, North by Northwest currently holds a 99% approval rating with the critical consensus reading as follows – ‘Gripping, suspenseful, and visually iconic, this late-period Hitchcock classic laid the groundwork for countless action thrillers to follow.’ I dare anyone to disagree with such a summation. The film remains fresh and utterly compelling some 60 years later because it’s effectively the perfect package on Hitchcock’s part whereby he drew upon the very best elements and qualities of many of his previous films with due regard for cinema-goers the world over. North by Northwest is sheer entertainment from first to last and it does not fade nor grow stale how ever many times you watch it (and I would suggest that 10 viewings is far too few for one lifetime). On an aesthetic and thematic level, the parallels with previous Hitchcock offerings are quite evident to see, and for the purposes of cross-referencing (if you are similarly inclined as myself), I would suggest the following films from the director’s canon – The 39 Steps, Foreign Correspondent, Saboteur, Notorious, To Catch a Thief and The Wrong Man. There are many other films from Hitch’s filmography which can also be related to his 1959 film, but these are the ones which stand out for me primarily. A quick word is also in order regarding Bernard Herrmann’s magnificent score (his fifth of seven collaborations with the director) and, of course, the memorable opening title sequence which was designed by the legendary Saul Bass. During a moment of considerable peril – while both of them are practically dangling from the face (faces) of Mount Rushmore – Eve Kendall enquires as to why Roger Thornhill’s previous two marriages did not work out. ‘They said I led too dull a life’ is the droll response she receives which, like so many unforgettable lines in this film, is both comic and forthright. There’s nothing in the least bit dull about this classic film six decades on since its first release and we duly salute it as one of the most entertaining thrillers of all time. A fantasy of the absurd for the ages.