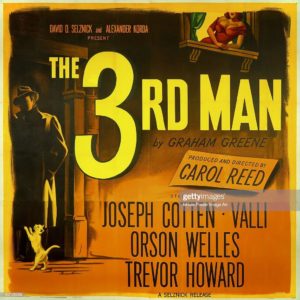

70 Years of The Third Man

Voted the greatest British film of all time (in a 1999 British Film Institute poll), Carol Reed’s The Third Man remains one of the best and most influential film noir/thrillers which has ever graced the silver screen. It’s 70 years since The Third Man was first released in the United Kingdom, but suffice it to say that this perennial classic has lost none of its visual impact or resonant storytelling in the intervening decades. Just what makes it so good? Well first of all there is the setting of post-war Vienna which lends the film its atmosphere of utter verisimilitude. Secondly, there is the stellar cast with wonderful performances all round, particularly those of Joseph Cotten, Orson Welles, Alida Valli (credited simply as Valli) and Trevor Howard. The taut direction of Reed and the uninhibited photography of Oscar-winner Robert Krasker (employing harsh lighting and Dutch angles aplenty) are outstanding elements on the technical side and one cannot possibly forget that haunting score by Anton Karas which seems to permeate every scene with its melancholy tone. Adapted by Graham Greene, from his novella of the same name, The Third Man also has a plethora of famous scenes and set-ups which reward repeated viewings and elevate the film’s iconic status. Small wonder so that the critical consensus on Rotten Tomatoes describes it as ‘one of the undisputed masterpieces of cinema.’

On the very subject of Anton Karas’s zither-led score, the legendary film critic Roger Ebert has – in a December 1996 article – suggested how this musical piece – first heard during the opening credits – perfectly sets the tone for what is to follow: beginning ‘like an undergraduate lark ‘ and then revealing ‘vicious undertones.’ The introductory narration, which is delivered by Reed himself, gives us some pertinent details about Vienna in the immediate post-war years. The Austrian capital, famed for its ‘Strauss music, its glamour and easy charm’, is divided into four zones, each occupied by a specific power (American, British, Russian and French). The Black Market has taken an immeasurable hold and racketeering is widespread and endemic. Into this sordid world comes one Holly Martins (Cotten), something of a proverbial innocent abroad, who, we are told, is the writer of pulp Western novels. Martins has been promised a job by his old friend Harry Lime and the narrator notes how he is ‘happy as a lark and without a cent.’ But then his plans go pear-shaped so to speak. Upon arriving at Lime’s address, Martins is informed that his old friend has been killed in a traffic accident. A burial service which he attends confirms as much. An alien in this strange city, Martins accepts a lift from a British officer named Calloway (Trevor Howard) who, subsequently, plies him with drink. Martins speaks of his friend in nostalgic terms, as one would do at such a moment, but then comes the first big revelation of the film: according to Calloway, Martins’s beloved friend was one of the worst racketeers in the city. The seemingly dispassionate authority figure even goes so far as to suggest that death was the best thing that ever happened to Harry Lime.

This heralds the theme of impossible loyalties which the film addresses among other things. Determined to clear his friend’s name, Martins decides to remain in Vienna and seek out those people who knew Harry intimately and transacted business with him. A troubling matter is the varied accounts of the accident which led to his death and the individuals who were present at the scene. ‘Baron’ Kurtz (Ernst Deutsch) and Dr. Winkel (Erich Ponto) relay different versions of this which appear to contradict each other and suggest a totally bizarre occurrence whereby Lime was accidentally killed by his own driver. The shady Popescu (Siegfried Breuer), on the other hand, is an altogether different proposition exuding charm and menace in equal measure. The presence of a third man at the scene of the accident becomes a minor obsession with Martins. Who was this mysterious man? Why has no one spoken to him about the incident? Lime’s girlfriend Anna Schmidt (Valli) has even fewer answers in this respect when Martins seeks her out at the theatre where she performs. But, crucially, she does suggest that Lime’s death may not have been an accident which causes Martins to question the porter at Lime’s place of residence. An argument ensues as the older man expresses his desire to be left alone fearing – as he does – serious consequences for himself. There’s a wonderful scene at this point involving a young boy who witnesses the heated exchange between Martins and the porter. Upon first viewing, you might well ask yourself what Reed and Greene’s intent is here – the answer becomes apparent just a short time later when the porter is murdered and Martins is accused of the crime by the boy.

A key decision taken by Reed with regard to the production was to film entirely on location in Vienna. Principal photography in the Austrian capital extended over a period of six weeks in 1948 and use was also made of the Sievering Studios in the city. The piles of rubble and treacherous craters which can be seen throughout the film lend a definite quality of authenticity to The Third Man. The post-war Vienna which Reed and cinematographer Robert Krasker present us with is a city which appears to have lost its way, perhaps even its soul. This is a world very much awry in comparison to conventional norms and societal expectations. Tainted by cut-throat survivalism and fraudulent trading, the former seat of the Habsburg Empire is contaminated by the immorality and decadence which seem universal. The currency of the Black Market is measured in both money and lives and the forces of occupation struggle to contain this whilst trying to maintain basic law and order. Watching the film with the benefit of historical perspective, one could suggest that The Third Man is a Cold War film – at the very least an early example of its representation. Roger Ebert has likened it to ‘the exhausted aftermath of Casablanca.’ The analogy is not unwarranted. As with the Michael Curtiz classic, we have the central character of an American exile who has been plunged into a world of duplicity and collusion. Martins is a flawed individual, but, unlike Bogart’s Rick Blaine, he does to his credit resolve to do the right thing at an early juncture in the film. There is also a romantic interest by way of a woman who has seen more than her fair share of the horrors of war. The Third Man’s Ilsa Lund is Anna Schmidt of course to whom Martins takes an immediate shine. Acutely aware of her continuing love for Harry, he downplays his own romantic prospects in one of the film’s best-acted scenes – ‘I’d make comic faces and stand on my head and grin at you between my legs and tell all sorts of jokes. I wouldn’t stand a chance, would I?’ He doesn’t stand a chance because Anna’s abiding devotion to Lime is one of the impossible loyalties which I referred to earlier. It becomes even more pronounced when the allegedly departed racketeer is revealed to be not quite as dead as the authorities and Martins had been led to believe.

Welles’s first appearance as Lime follows on from the disclosure (as provided by Calloway) that the latter had been supplying diluted penicillin which had resulted in several deaths and a host of medical complications for his victims. Despondent at such news, Martins decides to quit the city and return to America. A final visit to Anna suggests that she was aware of Harry’s malicious activities on some level. In a memorable shot of the darkened street outside her bedroom window, we watch as Anna’s cat rubs up against a shadowy figure. When Martins emerges from the building, he immediately assumes this is yet another police officer assigned to track him. Quite the reverse is shown to be the case as a light from a nearby window projects a shaft of light onto Welles’s familiar face. The Citizen Kane star shoots a warm smile at his old friend. Then he disappears into the night just as quickly. In terms of cinematic entrances, this is one of the most memorable and enigmatic in movie history. It’s a perfect moment wherein the story we have been following is flipped on its head and our suppositions are thrown into confusion. The first-time viewer will ask himself/herself how and why Lime is still alive. The answer to that very question returns us to the general malaise and wrongdoing which have infected the city. In a narrative context, Harry Lime serves as a personification of such misconduct. Bereft of any semblance of remorse, he has gone far beyond the pale of human decency. This becomes all the more apparent during the course of the famous Wiener Risenrad scene.

Having alerted Calloway to the fact that Lime is still very much alive, Martins looks on as the coffin is exhumed and another man by the name of Joseph Harbin – a hospital orderly who was assisting Lime by stealing penicillin – is discovered to be the real occupant (‘We should have dug deeper than a grave’). Seeking out a meeting with his former friend, Martins is directed to one of Vienna’s most iconic attractions, the Ferris wheel called the Wiener Risenrad which was constructed in 1897 (incidentally, the Risenrad has since featured in films such as 1987’s The Living Daylights and 1995’s Before Sunrise). Welles’s memorable performance as Lime confirms the prior suspicion that this is a man who no longer places any value on human life despite his protestation that ‘I still do believe in God old man. I believe in God and mercy and all that.’ When Martins presses him on his victims and the terrible suffering he has caused them (even death in some cases), Lime’s rejoinder is callous and couched in purely monetary terms – ‘Look down there. Tell me would you really feel any pity if one of those dots stopped moving forever? If I offered you twenty thousand pounds for every dot that stopped, would you really, old man, tell me to keep my money, or would you calculate how many dots you could afford to spare?’ Sliding open the door of their compartment on the wheel, Lime appears to insinuate that Martins is expendable like everyone else should he threaten to derail his business enterprise. It’s a chilling moment and it serves to demonstrate how perilous this relationship has become from Martins’s perspective. Lime at this moment represents the death of idealism as opposed to Martins’s fervent belief/hope that some sort of harmonious balance can still be restored – a storybook ending perhaps or a final act resolution. But this is not one of his Western novels as Calloway has previously warned him. The new world order has no place for would-be heroes such as him; Lime subscribes to such an outlook when he observes that ‘you and I aren’t heroes. The world doesn’t make any heroes outside of your stories.’

One of the principal concepts which the film examines is the idea that the individual can no longer bend matters to his own will in the absence of an illegal undertaking. Holly Martins, the pulp Western writer, discovers, to his considerable frustration, that the so-called rules of the Old West have no currency in this murky world. The ineffectiveness of Martins as the would-be hero is highlighted throughout the film – he gets drunk and argumentative at an early point (Bernard Lee’s Sergeant Paine subdues him with a punch to the face); he is shown up to be quite inadequate as a speaker at a book club meeting (organised by Wilfrid Hyde-White’s Crabbin); he ultimately fails to redeem his fallen friend; and, to all appearances, he does not manage to win the girl in the end. His romantic notions are entirely misplaced until he comes face to face with Lime on the Ferris wheel and it’s only following this encounter that he takes a modicum of decisive action – but even then he has to be induced by Calloway (who shows him first-hand some of the brain-damaged children who have been administered Lime’s diluted penicillin). Martins is no champion of a particular cause or idea, rather he is something of a grown-up child evidently confronted by the harshness of the world for the very first time. ‘Happy as a lark’ when he first gets off the train in the Austrian capital, is he also an embodiment of the ‘optimism of Americans’ after the war as opposed to the ‘bone-weariness of Europe’ as Roger Ebert terms it? In any event, my suggestion here is that he is far from being the epitome of a hero; neither a white knight nor a rugged warrior of the prairies, his most emphatic act in the whole film is to mercy-kill his injured friend in the darkened sewers beneath the streets of Vienna. Not quite the actions one would equate with an intrepid protagonist.

The film’s downbeat ending – which Greene himself did not want, but which Reed correctly insisted upon – takes place in the same cemetery following Lime’s actual death. Passing by the grieving Anna in Calloway’s jeep, Martins requests to be let out so that he might – what we wonder – speak words of comfort to her? Offer her an embrace of consolation? Standing under a tree, he waits for her, but his hopes of an immediate reconciliation are dashed as she walks past him out of frame. Martins lights a cigarette and throws the match away in an apparent expression of despair. Has a feeling of hopelessness engulfed him now as well we ask ourselves. Certainly, a feeling of bleakness is the prevailing one at the film’s conclusion. This is not a happy ending, rather a melancholic one, and it’s entirely in keeping with the film’s tone and subject matter. The post-war world (Vienna is its microcosm) is a much altered state (and that refers to states of mind as well). There is no place in this new reality for wishful thinking or romantic sentiment. Suspicion and cynicism are the order of the day now. Much as he might want to protect Anna and love her, Martins is only too aware of her devotion to a dead man – a dead man who caused the deaths and impairment of others. No grandiose gesture will suffice in this particular domain. Martins’s discarding of the match suggests that he may have given up on hope like so many others. At the time of filming, Joseph Cotten said that he thought the scene in question would end much sooner; however, Reed kept the camera running long after Valli had departed the shot and the resultant effect is one of lingering sadness. It constitutes a ‘long, elegiac sigh’ in the words of Roger Ebert and we can only be eternally grateful that Reed got his way on this indelible ending. The final chords of Karas’s score hang in the air reflecting a generally doleful mood.

The Third Man’s best-known and most revered moment is undoubtedly Lime’s cuckoo clock speech as he and Martins alight from the Wiener Risenrad. Appearing to search for a justification with respect to the human suffering which he has left in his wake, Lime attempts to frame his pernicious endeavours (and those of others no doubt) in a historical context. Is he suggesting that some great aesthetic movement will come about because of the chaos and disorder they contribute to? Certainly, the implication seems to be that art and high culture will not be sufficiently stirred in the absence of some degree of societal turbulence; the greater the anarchy, the greater the proclivity towards artistic pursuits – ‘You know what the fellow said, in Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love, they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.’ Welles is largely credited for writing this speech himself, but he is said to have acknowledged that the source of the rumination came from an ‘old Hungarian play’ – hence his reason for beginning the speech with the phrase ‘You know what the fellow said.’ Welles – an American himself – may well have understood that the filmmakers were imparting an underlying message about American hegemony in the post-war world. Greene, in particular, a former member of MI6, would surely have grasped the new world order for what it was and even anticipated the vigorous role which America would strive to confer upon herself (as leading nation of the free world). Although ineffectual for the most part, Martins is nonetheless well-intentioned and herein may lie the implicit warning from the ex-spy: aspirations – even dreams – are all well and good, but they are no substitute for fundamental knowledge and experience. In this latter regard, Trevor Howard’s Calloway is the one constant character in the film – the resolute arm of the law who understands his place in the world and determines to make a difference come what may. If a sequel had been made, we could well imagine the policeman still there in Vienna pursuing miscreants such as Lime. Martins, on the other hand (and in the absence of Anna’s affections), seems more likely to return home and resume his Zane Grey-like novels.

70 years on from its initial release, The Third Man more that stands up to repeated viewing and fully deserves its recognition as one of the best films of all time. It’s interesting to note that this was the second of three collaborations between Carol Reed and Graham Greene over the course of their respective careers – the first was 1948’s The Fallen Idol (based on the short story The Basement Room by Greene) which earned Oscar nominations for both Reed as Best Director and Greene for Best Adapted Screenplay. Their third and final film together came by way of 1959’s Our Man in Havana based on the 1958 novel of the same name by Greene. Noel Coward – who, incidentally, was first suggested for the part of Harry Lime by producer David O. Selznick – appears in this latter film alongside the likes of Alec Guinness, Ralph Richardson and Maureen O’Hara. There’s little doubt however that both men hit cinematic peaks with The Third Man, a film which perfectly captures a cynical post-war world on the cusp of the Cold War. Blessed with some remarkable central performances, a wonderful and witty script, exemplary direction, haunting photography and an imperishable score, The Third Man continues to endure to this day as one of the masterpieces of world cinema. Watch it again and be reminded of how great the medium of motion picture can be.