Happy 75th Birthday Martin Scorsese – 15 Of His Best Films

The great Martin Scorsese celebrates his 75th birthday on November 17th, 2017 and we look back with much admiration on a career in film which has produced some true classics of cinema beginning with his work behind the camera in the late 1960s. Scorsese has carved a reputation for himself which places him among the elite of world cinema and marks him out as a true visionary of this art form. Beginning with his first feature length film in 1967 – Who’s That Knocking at My Door – the director has explored a myriad of themes which include his own personal Catholic background, faith, redemption, gang violence, mob influence and male machismo. For many, his best films are searing examinations of crime in an urban context which seems almost all pervasive and above the proper boundaries of social justice. 1973’s Mean Streets, for example, involves a protagonist who seeks to be inherently honourable in such a corrupt and depraved world; the eventual failure of his enterprise at the film’s end suggests that the individual can change little when faced down by more powerful forces which include social convention and an established way of life. In stark contrast to this is the ending of his 1990 masterpiece Goodfellas in which the central character Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) laments the fact that – bereft now of the glamorous lifestyle he used to lead – he has become nothing more than an ‘average nobody.’

The writer-director has rightly been praised for his visual style in films such as 1980’s Raging Bull and 1991’s Cape Fear. Scorsese is himself an acknowledged student and historian of world cinema who went to the movie theatre on a frequent basis whilst other boys his age played sports. He lists films such as John Ford’s The Searchers and Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo among his favourites. Pivotal films in his own career would surely have to include 1976’s Taxi Driver and 1980’s Raging Bull. Both films paired Scorsese with actor Robert De Niro (with whom he has made eight films to date) and are especially noteworthy with respect to the degree of brutality portrayed on screen juxtaposed with a pseudo-redemptive quality which permeates – Travis Bickle is severely wounded as he rescues the young Jodie Foster at the climax of Taxi Driver; in Raging Bull Jake LaMotta seeks to atone for his sins by allowing Sugar Ray Robinson to almost beat him to a pulp in the ring.

The filmmaker has had his own personal ups and downs over the years and his career hit some barren periods occasioned by misfires such as 1977’s New York, New York which proved to be a commercial failure. He recovered much ground by way of Raging Bull in 1980 and The King of Comedy in 1983, but did not experience a box office success in the strictest sense until 1991’s Cape Fear which, itself, was a remake of the J. Lee Thompson film of the same name. The rest of the 1990s was something of a mixed bag for the director with respect to films such as 1993’s The Age of Innocence and 1997’s Kundun, but he fared much better in the early to mid 2000s by way of more populist entertainments such as Gangs of New York, The Aviator and The Departed (which earned him his first and only Best Director Academy Award to date).

Scorsese’s most recent films (that is in the last ten years) have included Shutter Island, Hugo, The Wolf of Wall Street (his fifth collaboration with actor Leonardo DiCaprio) to date and – most recently – 2016’s Silence which returned him to the world of religion and faith. He is currently working on a project titled The Irishman which is tentatively due for release in 2019; previous collaborators of his Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci and Harvey Keitel are among the cast; Al Pacino plays the role of the infamous union leader Jimmy Hoffa. As the filmmaker approaches the midpoint of his 70s, we wish him many more years of success and hope to see him realise some of the projects he has mapped out for himself which include (at time of writing) biopics on American presidents George Washington and Teddy Roosevelt. It’s time, however, to look back now on Scorsese’s career to date and, to this end, I’ve selected fifteen of his best films ranging from the years 1973 to 2013. Happy 75th Marty. Long may you continue to illuminate the world of cinema.

Mean Streets (Martin Scorsese 1973)

As was the case with 1967’s Who’s That Knocking at My Door, Scorsese again explored themes of Catholic guilt and the individual’s dilemma as he tries to do the right thing in a world of conflict and contradiction. Charlie (Harvey Keitel), a young Italian-American living in New York City, has a bright future ahead of him if he plays the game properly. The nephew of the local capo, Charlie collects debts on behalf of his uncle and is respectable and trustworthy to all appearances. But he lives a double life of sorts. Involved in a relationship with a sickly woman named Teresa (Amy Robinson), Charlie also feels a peculiar responsibility towards her wayward and unpredictable cousin Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro). Johnny Boy owes money all over town and Charlie is at a loss as to how to direct him back to the straight and narrow. He seeks his answers to this and other problems in the church, but realises only too well that the harsh and violent streets of his neighbourhood may be a more powerful and exacting influence – ‘You don’t make up for your sins in church. You do it in the streets. You do it at home. The rest is bullshit and you know it.’ Following on from the tepidly received Boxcar Bertha of the previous year, this is Scorsese’s first great film and it owes its success to several factors including his direction and the finely observed screenplay he co-wrote with Mardik Martin. A critical decision by the director in this case was to tell a story about characters he knew and experiences he had growing up in Manhattan’s Little Italy. A stark choice of either embracing a life of crime or religion in such a milieu is one which Scorsese has often mentioned and it comprises the inner turmoil which his central character feels. Keitel is superb as Charlie, but it’s De Niro who really catches the attention here as the reckless and self-serving Johnny Boy. David Proval – who would later play Richie Aprile in The Sopranos – features as one of Charlie’s best friends. The late David Carradine turns up as a drunk in one of the film’s many striking sequences. The ‘mook’ scene is also particularly memorable and a hoot as well. Scorsese narrates and appears as a gunman in the film’s climactic finale. Not surprisingly, it’s a rather bloody denouement which is in keeping with the director’s vision and the film’s overarching theme of sins being atoned for on the titular Mean Streets. Scorsese had truly arrived and critics and audiences alike began to pay him far greater attention.

Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (Martin Scorsese 1974)

Scorsese displayed his versatility behind the camera a year after Mean Streets as he delivered this sensitive and oft-humorous tale about a woman re-inventing herself as she strives for a new and better life. Alice Hyatt (Ellen Burstyn) is a former singer trapped in a rather loveless marriage. When her husband Donald dies suddenly in an accident, Alice determines to move back to her childhood hometown of Monterey along with her young son Tommy. Her plans and ambitions veer slightly off course as her finances dwindle and she is forced to take a job as a waitress in Tucson. There she meets David (Kris Kristofferson), a divorced local rancher, who has a steady influence on Tommy and is no-nonsense with respect to his affections for her. In the wake of her success in both The Last Picture Show and The Exorcist, Burstyn was Hollywood hot property at the time, but she was anxious that Alice be given to a director who could invest the film with a real-world tone. Burstyn credits Francis Ford Coppola as being the one who suggested Scorsese in this regard and the actress was suitably enthused upon viewing his Mean Streets. The collaboration was a rewarding one for both actress and director; Scorsese, in particular, demonstrated that he could step into other film genres to great effect. Burstyn, for her part, went on to win the Academy Award for Best Actress; Alice itself won the BAFTA Award for Best Film. Diane Ladd and Valerie Curtin are especially memorable as Alice’s work colleagues in the diner in Tucson. Harvey Keitel and Jodie Foster also turn up in supporting roles. Foster would feature to even greater effect in Scorsese’s very next film.

Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese 1976)

‘You talkin’ to me? You talkin’ to me?’ Robert De Niro enquires of an imaginary figure in this film’s most referenced and iconic moment. De Niro plays Travis Bickle, a former U.S. Marine who cannot sleep at night and decides to become a taxi driver in order to cope with his chronic insomnia. Travis’s sense of isolation (‘I’m God’s lonely man’) and his general disaffection with the world around him (the city of New York which he feels should be flushed ‘down the fucking toilet’) become even more pronounced as he views the lowlifes and the phonies who inhabit it. Rebuffed by the gorgeous Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), and disgusted by the pimp ‘Sport’ (Harvey Keitel), who personifies the baseness of this urban milieu, Travis determines upon a course of action which he hopes will shock society out of its moral torpor. Scorsese has spoken about Taxi Driver employing familiarly religious connotations. For him Travis is like ‘an avenging angel’ who wishes to cleanse himself by means of a tangible act. Screenwriter Paul Schrader was himself in a bad personal place whilst writing the script and cites Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground and An Assassin’s Diary by Arthur Bremer as being key influences. The climactic shoot-out – in which Travis attempts to rescue child prostitute Iris (Jodie Foster) from the clutches of ‘Sport’ – raised more than a few eyebrows with respect to its graphic violence; in order to secure an R rating for the film Scorsese de-saturated the colour and later acknowledged that the scene works better in this particular hue. And as for Taxi Driver’s ultimate ending, there has been extensive debate as to its significance and ramifications for the plot as a whole. Has Travis’s misconstrued act of heroism provided him with the peace of mind and sense of purpose he has been seeking all along? Will he revert to a normal socially-acceptable life now that he has redeemed himself? Some critics even argue that this sequence is but a further extension of the character’s twisted mind. What seems evident to me is the fact that Travis remains a marginal figure who may yet again descend into the morass his mind had brought him to in the first place. Scorsese suggests as much with a telling shot in which the recuperated taxi driver catches a glimpse of himself in the mirror and quickly looks away. Nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Actor and Best Picture, Taxi Driver secured the Palme d’Or for Scorsese at the 29th Cannes Film Festival. The highly memorable score was one of the last by veteran composer, and Hitchcock regular, Bernard Herrmann. Watch out also for a cameo by Scorsese himself playing a passenger in Travis’s cab who insists on observing his cheating wife – ‘I’m gonna kill them. There’s nothing else. I’m just gonna kill them. And what you think of that?’ What we think is that this 1976 classic is one of the director’s very best.

Raging Bull (Martin Scorsese 1980)

My own personal favourite of the director’s, Raging Bull also features in my Top Ten films of all time. Scorsese was reluctant to say the least about making the sports bio based on the life and times of middleweight boxer Jake LaMotta. Robert De Niro was instrumental in the inception of the project – having read LaMotta’s warts and all autobiography Raging Bull: My Story – and pressed his frequent director to get himself involved. Suffering from poor health at the time, and a loss of confidence following the box office failure of 1977’s New York, New York, the director balked at the notion of the sports drama stating that he had no interest in this particular area. Thankfully, De Niro prevailed and Scorsese agreed to sit in the director’s chair once again. Convinced that this would be his final film, Scorsese set about his task with a characteristic eye for realism and meticulous detail. The fight scenes were choreographed to a methodical style and linger long in the memory in terms of their impact. A crucial decision by the director was his insistence that the ring scenes be shot inside the ring itself in order to convey the power and oft-brutality of the sport. In the peak of physical fitness for his role, De Niro engaged a punching bag between takes before moving on to the next scene. In startling contrast to this is his later Jake, the retired boxer who has gained too much weight and become indolent with respect to his body and his relationship with his wife and kids. De Niro famously embarked upon an eating binge in Northern Italy and France to gain some seventy pounds and the resulting transformation is one of the most striking in all of cinema. This is quite simply the greatest sports film ever made and thoroughly deserves its place at the top of the American Film Institute’s list of such movies. Memorable – and haunting scenes – include LaMotta allowing himself to be pummeled by Sugar Ray Robinson in a seeming act of contrition regarding his estranged brother Joey (Joe Pesci) – ‘You never got me down Ray. You never got me down man.’ Equally powerful and somehow poignant is the jail cell head-banging scene in which the overweight and pitiable LaMotta cries following his incarceration – ‘I’m not an animal!’ For me De Niro’s performance (which earned him the Academy Award for Best Actor) is probably the greatest of all time. In terrific supporting roles Joe Pesci and Cathy Moriarty (as Jake’s second wife Vikki) also excel. Regarded as one of the greatest films of all time, Raging Bull cemented Scorsese’s status as an artist of some stature and unquestionable merit. The director himself cameos late in the film as an unseen stagehand telling Jake he is due to go on. This is the high point of his career and indeed that of his leading man as well. Uncompromising and unputdownable, the film is appropriately dedicated to Haig Manoogian, the NYU film professor who had a major influence on Scorsese’s career.

The King of Comedy (Martin Scorsese 1983)

A very dark comedy from the director indeed in which the themes of celebrity worship and the power of media culture are explored. The King of Comedy may have been made in the early 1980s, but it has a continued relevance to this day and remains fresh no matter how many times you view it. De Niro plays Rupert Pupkin an aspiring stand-up comedian who has delusions of fame and fortune. Much of his fantasy world centres on his idol Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis) with whom he imagines he has a personal and professional bond. Langford’s staff are understandably uneasy as Pupkin hangs out at the office expecting a meeting with their boss, and Langford himself is less than impressed when the persistent Pupkin shows up uninvited at his country house. Aided by the similarly obsessed Masha (Sandra Bernhard), Rupert settles on an extreme course of action and kidnaps Langford. In exchange for the safe return of the talk show host, he requests that he be given his fifteen minutes of fame – a slot for his own comic routine on that evening’s show hosted by Tony Randall. Not widely praised on its initial release, The King of Comedy now deservedly ranks high in the Scorsese/De Niro canon. It’s a wonderful satire bolstered by the performances of De Niro, Lewis and Bernhard. A stand-out scene is the aforementioned country house one in which an irate Langford tells Pupkin to leave his property and to desist from further such acts – in order to draw a suitably enraged response from his co-star Lewis, De Niro apparently hurled a plethora of anti-Semitic remarks his way. Scorsese cameos once again playing the part of a director on the Jerry Langford Show; his mother – Catherine Scorsese – provides the voice of Rupert’s unseen mother. Essential viewing for fans of the director and of the leading man.

The Color of Money (Martin Scorsese 1986)

Paul Newman reprised his role as Fast Eddie Felson and won a long overdue Oscar in this fine follow-up to 1961’s The Hustler. It’s been a quarter of a century since Fast Eddie was told that he’d never ‘walk into a big-time pool hall again,’ but this is indeed where we find him at the beginning of the film. Eddie has become a successful liquor salesman, but he still likes to dip his toes as a stakehorse. When he comes upon a highly talented pool player by the name of Vincent Lauria (Tom Cruise), Eddie sees something of himself in the kid’s brashness and skill at the nine-ball game. Determining to impart some of his own considerable wisdom to the up-and-comer, Eddie convinces Vincent and his streetwise girlfriend Carmen (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) to go on the road with him. The venture has its ups and downs and culminates in a nine-ball tournament in Atlantic City. Adapted from the 1984 novel of the same name by Walter Tevis (who also wrote The Hustler), The Color of Money differs quite markedly from its source material and does not feature the character of Minnesota Fats. Scorsese said that Jackie Gleason – who played Fats in the 1961 film – was approached with a draft of the script which included his character, but subsequently declined. Richard Price’s final script builds well on the relationship between Fast Eddie and Vincent picking out the sources of tension and commonality. Newman is in typically superb form as the man who has seen it all; as the conceited Vincent, Cruise proved that he was more than a pretty boy. It’s not quite in the same league as The Hustler, but The Color of Money benefits from elements such as Scorsese’s direction, the performance of its cast and the rapid-fire editing of the director’s long-time collaborator Thelma Schoonmaker. The supporting players include John Turturro and Forest Whitaker. Another Scorsese regular Robbie Robertson (of The Band fame) provides the original score.

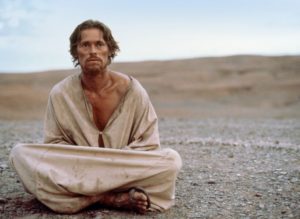

The Last Temptation of Christ (Martin Scorsese 1988)

Scorsese had yearned to make a film about the life of Christ for many years particularly in light of his admiration for biblical epics such as Nicholas Ray’s 1961 King of Kings. Based on the controversial 1955 novel of the same name by Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis, The Last Temptation of Christ was also the subject of much derision and protest upon its theatrical release in 1988. Christian groups objected most especially to the film’s final third in which a crucified Jesus (Willem Dafoe) is apparently given the opportunity to live a normal secular life. He does so and takes several wives including Mary Magdalene (Barbara Hershey). The consummation of his marriage to the latter character was a source of particular friction and several countries, including Mexico, Argentina and Greece, banned or censored the film for many years after its initial run. Adapted by Paul Schrader, the central premise of The Last Temptation of Christ is to depict a Messiah who is emotionally torn and filled with self doubts. He is a man prone to weakness and temptation as the very title suggests; he is acutely aware of his own limitations and human mortality; ultimately, he wishes to survive and prosper as best he can. A superb performance by Dafoe in the central role conveys the sense of personal turmoil he experiences when faced with the daunting mission God has set for him. Shot entirely on location in Morocco, The Last Temptation of Christ was deeply divisive in its day, but the passage of time has proven what an honest and sincere portrayal it is. Bereft of the pomp and circumstance which have accompanied other such films in this genre, it deserves its place among the very best which include Pasolini’s The Gospel According to Matthew. Scorsese deservedly received an Academy Award nomination for best director for his sizable efforts. The supporting cast includes Harvey Keitel as Judas Iscariot and David Bowie as Pontius Pilate. Peter Gabriel’s excellent original score has a suitably melancholic aspect to it which harmonises with the film’s ultimate message of duty and sacrifice.

Goodfellas (Martin Scorsese 1990)

As far as the gangster/crime genre goes, Scorsese hit his peak with this adaptation of the 1986 non-fiction book Wiseguy by author Nicholas Pileggi (who also collaborated on the screenplay with Scorsese). Chronicling the life and illegal escapades of mob associate Henry Hill over a 25-year period, Goodfellas remains one of the director’s very best and has not in the least bit aged or grown less relevant with the passage of time. Beginning with an impeccable sequence in which Billy Batts (Frank Vincent) is finished off by the trio of Henry (Ray Liotta), Jimmy Conway (Robert De Niro) and Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci), this is film-making of the very highest order imparting, as it does, the age-old story of the character who is lured by the seeming glamour and prestige of the underworld. It’s in that opening line as uttered by Henry (‘As far back as I can remember I always wanted to be a gangster’) and documented as he rises in rank by means of petty crime and the Air France robbery in 1967. Scorsese relays the exhilaration of a lifestyle which is constantly perilous and never predictable by means of rapid-fire dialogue, a memorable soundtrack (the songs which he chose himself) and typically brilliant editing by Thelma Schoonmaker. There are so many standout scenes throughout the film that it’s not possible to list them all here, but allow me to make special reference to the ‘Funny how?’ exchange between Liotta and Pesci, the aforementioned Billy Batts scene and his subsequent disposal (‘Here’s a leg! Here’s a wing!), the entirety of the 11th May, 1980 sequence as a nervous and cocaine-addicted Henry is tailed by the authorities, and the glorious unbroken tracking shot of Henry and Karen (Lorraine Bracco) as they enter the Copacabana Nightclub at an early point in the story. Scorsese intended this shot to symbolise how such a high-flying lifestyle seduces his characters and makes them do things they might otherwise have never contemplated. At the film’s close – when Henry regrets the passing of his previous existence (‘I’m an average nobody’) – Scorsese said he hoped the audience ‘would get angry with him…and maybe with the system which allows this.’ For all its attendant style and visual flair, Goodfellas also holds up to the light the more sordid and less desirable aspects of this life of crime. There are no heroes here ultimately. Henry gives up Jimmy and Paulie (Paul Sorvino) in order to save his own skin. With exceptional performances (among them an Oscar-winning turn by Joe Pesci) and a breakneck visual rhythm which permeates the piece, Goodfellas is without doubt one of the greatest American crime films. The AFI ranks it second-best of all time, just one place behind 1972’s The Godfather. The Sopranos creator David Chase credits it as the inspiration for that television series stating in no uncertain terms that ‘Goodfellas is the Koran for me.’

Cape Fear (Martin Scorsese 1991)

Scorsese ventured into the psychological-thriller genre in this a remake of the 1962 film of the same name which was directed by J. Lee Thompson. Based on the 1957 novel The Executioners by John D. MacDonald, Cape Fear tells the story of one Max Cady (Robert De Niro), a once illiterate and convicted rapist who – upon his release following 14 years incarceration – is intent upon exacting revenge on his defense lawyer Sam Bowden (Nick Nolte) whom he has discovered withheld evidence which might have led to his release. The seventh of eight collaborations to date between actor and director, Cape Fear is effectively Scorsese’s homage to directors such as Alfred Hitchcock and films such as the original Cape Fear and Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter. Cameo appearances by original Cape Fear stars Robert Mitchum, Gregory Peck and Martin Balsam tip their hat in such a regard as does Scorsese’s employment of the original score by Bernard Herrmann. De Niro is in fine form as the compulsively-driven Cady, but he’s also well supported by Nolte, Jessica Lange and the young Juliette Lewis (who received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress). Cape Fear may not be the director’s most subtle work, but the style and tempo he adapts here do have a purpose which is to give the film its inflated and hyper-dramatic atmosphere. The climactic storm sequence is an example of this demonstrating Scorsese’s ability to work with a larger budget and special effects. Cape Fear was a box office success and – taken in combination with the critically-acclaimed Goodfellas – provided the director with a much welcome impetus at the beginning of the 1990s. You also just have to love The Simpsons 1993 parody of the film which was appropriately titled Cape Feare.

Casino (Martin Scorsese 1995)

Not as well received upon its initial release as it deserved to be (Goodfellas goes west was one such derisory summation), this 1995 crime-drama concerns itself with mobster goings-on in the Entertainment Capital of the World. Based on the non-fiction book Casino: Love and Honor in Las Vegas by Nicholas Pileggi, Casino focuses on the character of Sam ‘Ace’ Rothstein (Robert De Niro) who was based on the real-life Frank ‘Lefty’ Rosenthal. Called upon by the Italian mob to oversee their operations at the Tangiers Casino in Vegas, Rothstein becomes a most effective administrator as he doubles profits in a short space of time whilst allowing the skimming of such revenue prior to its declaration to the tax authorities. As is so often the case in such a universe, the personal and intimate soon become a sizable distraction – Ace is besotted by a former prostitute named Ginger McKenna (Sharon Stone in an Oscar-nominated performance) who is avaricious and self-serving. They marry and he attempts to sustain the relationship with inflated affection and priceless gifts. On a professional level, the arrival of the volatile Nicky Santoro (Joe Pesci) is also problematic. Although childhood friends, the two clash in relation to method. The pragmatic Ace wishes to keep business on a even footing; the more ambitious and daring Nicky has other ideas. One of the most striking features of Casino is its level of detail with respect to the gaming industry and the shady dealings which were going on in the background during this particular period. As always, Scorsese’s meticulous attention to detail is second-to-none and he’s aided and abetted here by his Goodfellas co-scriptwriter Pileggi. Perhaps it’s the very names of Scorsese, Pileggi, De Niro and Pesci which caused Casino to be likened so much to the earlier film. In terms of genre, style and setting the films certainly are not poles apart, but, although the slightly inferior of the two, Casino nevertheless deserves to be appraised on its own particular merits. James Woods, Don Rickles and Kevin Pollak are among the supporting cast. Frank Vincent (who’d previously featured in Raging Bull and Goodfellas) finally got the opportunity to beat on Joe Pesci – watch all three films and you’ll see exactly what I mean.

Gangs of New York (Martin Scorsese 2002)

Scorsese first came across Herbert Asbury’s The Gangs of New York: An Informal History of the Underworld in the early 1970s and was duly intrigued by its narrative of the nascent city’s criminals as they strove and battled for its mastery. ‘The country was up for grabs, and New York was a powder keg,’ he noted in connection with the conflicts between the Nativists and Irish Catholic immigrants. At heart a story of revenge, Gangs of New York focuses on the character of Amsterdam Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio) as he pursues his father’s killer William Cutting (Daniel Day-Lewis), or Bill ‘the Butcher’ as he is better known. Ingratiating himself gradually with Cutting, Amsterdam determines to exact his vendetta on the anniversary of the battle of the Five Points at which his father ‘Priest’ Vallon (Liam Neeson) was slain. During the course of its 168-minute running time, Scorsese and his writers (Jay Cocks, Steven Zaillian and Kenneth Lonergan) also document many of the social mores and class predispositions of the day. An incredibly ambitious project from its very inception, Gangs of New York was shot at Rome’s Cinecitta Studios where production designer Dante Ferretti recreated over a mile of mid-nineteenth century New York buildings. Unsurprisingly, such detail and meticulous design contributed to the film’s escalating costs and overrun production period which brought Scorsese into conflict with his producer Miramax’s Harvey Weinstein. The film eventually cost $100 million and was not released until 2002. It’s far from vintage Scorsese, but Gangs of New York does benefit from its period detail, the cinematography of Michael Ballhaus and a stellar cast which includes DiCaprio, Neeson, Brendan Gleeson, John C. Reilly and Jim Broadbent. Towering above these in terms of his performance is, of course, Day-Lewis as Bill ‘the Butcher.’ U2 picked up one of the film’s 10 Academy Award nominations for the song The Hands That Built America. A flawed, violent and often overblown piece of cinema which has its particular place in the director’s overall body of work.

The Aviator (Martin Scorsese 2004)

Scorsese re-teamed with star DiCaprio for this biographical film concerning American businessman, pilot, director and philanthropist Howard Hughes. Focusing on a portion of his life (1927 to 1947), the screenplay by John Logan essays Hughes’s days as a filmmaker in Hollywood as well as his burgeoning interest in aviation generally. DiCaprio is in top form as the eccentric billionaire who was afflicted by severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. Other notables among the cast include Alan Alda, John C. Reilly, Danny Huston and Alec Baldwin. Jude Law plays Hollywood legend and general hell-raiser Errol Flynn; Cate Blanchett won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her studied performance as Katharine Hepburn. A fine reflection on a passed era and a troubled genius, The Aviator – like Gangs of New York – benefited greatly from the art direction of Dante Ferretti and the set decoration of Francesca Lo Schiavo (who won an Oscar for Best Art Direction). Golden gongs were also awarded to Robert Richardson for Best Cinematography, Sandy Powell for Best Costume Design and Thelma Schoonmaker for Best Film Editing. The picture lost out at that year’s ceremony to Clint Eastwood’s Mullion Dollar Baby. With typically assured direction, Scorsese played his part here in rescuing and enhancing Hughes’s legacy in the aviation field; he also offers us a glorious snapshot of Tinseltown during its Golden Age. But most compelling of all are the innermost scenes in which Hughes figuratively descends into a type of madness and incessant fixation. DiCaprio, to my mind, came of age as an actor in this particular instance. Two years later he would collaborate with Scorsese once again on the film referenced directly below. A fine period piece and a partnership between actor and director that was truly beginning to find its feet.

The Departed (Martin Scorsese 2006)

Scorsese finally won his long overdue Best Director Oscar for this 2006 crime-drama film which is a remake of the 2002 Hong Kong film Infernal Affairs. Retaining the central premise of that earlier work, The Departed is set in contemporary Boston and concerns a mole in the police department and an infiltrator in a crime outfit. Matt Damon and Leonardo DiCaprio play the respective parts and the screenplay by William Monahan accentuates the tension suitably as both sides come to understand this quite unique situation. Jack Nicholson plays Irish-American mobster Frank Costello and the actor himself reputedly came up with the idea of basing this character on the real-life Whitey Bulger who also, incidentally, hailed from Boston. A superb Mark Wahlberg all but steals the show as the straight-talking and foul mouthed Staff Sergeant Sean Dignam (‘I’m the guy who does his job. You must be the other guy’). Among the supporting cast also are the likes of Alec Baldwin, Ray Winstone, Vera Farmiga and Martin Sheen. Although set in Boston, The Departed was mostly shot in New York City which had more favourable tax incentives available for filmmakers at the time. Winner of four Oscars in total (including Best Film and the aforementioned Best Director), The Departed has been somewhat unfairly regarded as a lifetime achievement award for Scorsese following six previous losses. It’s certainly not in the same class as Goodfellas, Raging Bull or Taxi Driver, but this is a fine populist entertainment from a director who is entirely in control of his medium and at one with his craft. Upon winning his Academy Award, the director himself joked that, ‘This is the first movie I’ve done with a plot.’ A typically rousing score features Comfortably Numb by The Band and I’m Shipping Up to Boston by the Dropkick Murphys. The rat, which appears in the final scene, was acknowledged by Scorsese as representing the search for the ‘rat’ throughout the film; this was in keeping with the themes of trust and allegiances which are explored in the story. Not quite a Scorsese classic, but an excellent entry in his canon nonetheless.

Hugo (Martin Scorsese 2011)

More than a few eyebrows were raised when Scorsese announced his involvement in this particular project. Based on the 2007 book The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick, this concerns itself with the story of a young boy who lives in the Gare Montparnasse railway station in Paris in the 1930s. Orphaned at much too early an age, the titular character occupies his time by maintaining the clocks in the station, eluding the clutches of the wily Inspector Gustave (Sacha Baron Cohen) and seeking to repair a broken automaton which his late father (Jude Law) had been working on. Assisted in his quest by Isabelle (Chloe Grace Moretz), Hugo stumbles upon the true identity of her Papa Georges (Ben Kingsley), a crotchety toy store owner, who is none other than the famous illusionist and pioneering film director Georges Melies. With this in mind, it has to be said that Hugo is one of Scorsese’s most personal films giving prominence, as it does, to the themes of art, entertainment, the enduring magic of movie-making and the importance of film preservation. The first film of Scorsese’s shot in 3D, and hailed by James Cameron as a ‘masterpiece’ in this respect, Hugo received 11 Academy Award nominations (including Best Picture and Best Director) and won in five technical categories. And yet the film was something of a box office disappointment – perhaps, unfortunately, it fell between two stools as regards its target audiences – a little too sophisticated and culture-referencing for younger members; too personal and heartfelt on the director’s part for those of an older age. Roger Ebert summed the film up well when he reflected in his review that it was ‘possibly the closest to his (Scorsese’s) heart.’ With regard to the aforementioned 3D process, the director himself remarked ‘I found 3D to be really interesting because the actors were more upfront emotionally.’ The cast in this case included others such as Ray Winstone, Emily Mortimer, Michael Stuhlbarg and the legendary Christopher Lee. The scene in which Hugo hangs from the hands of a large clock whilst being pursued is typical of the cinematic reverence on display here, referencing, as it does, Harold Lloyd’s antics in Safety Last. A loving tribute indeed and a visually sumptuous film on Scorsese’s part.

The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin Scorsese 2013)

Based on the book of the same name, Scorsese’s fifth collaboration with Leonardo DiCaprio focuses on the life and shady dealings of one Jordan Belfort, a stockbroker of modest beginnings who rose by means of guile and ruse. Beginning in the late 1980s, The Wolf of Wall Street chronicles Belfort’s career as he ventures into the penny stocks market. Realising the untapped potential of this particular sector, Belfort’s star ascended in double-quick fashion just as his methods became increasingly unscrupulous and self-serving. DiCaprio is perfectly cast as the highly ambitious Belfort who considers himself above the law and beyond moral reproach and he’s well supported by a cast which includes Kyle Chandler, Jonah Hill, Margot Robbie and Matthew McConaughey. Generally well received by critics and audiences (and the recipient of five Academy Award nominations), The Wolf of Wall Street was, however, not without its detractors who questioned its morally ambiguous position and frequent use of profanity. The adapted screenplay by Terence Winter (of The Sopranos and Boardwalk Empire fame) is estimated to contain a record use of the word ‘fuck’ in a mainstream film and more conservative viewers also objected to the excessive near-hedonistic lifestyles on display here. The point, of course, is an entirely valid one. Belfort was a convicted criminal who served three years in a minimum security prison. His avaricious nature and illegal approach to business was costly to many others and he scarcely considered the implications of his activities. Such a mindset is exemplified in the scene in which Belfort wantonly tosses money at FBI agent Patrick Denham and his partner. The hilarious and much-talked about quaalude scene involving DiCaprio and Hill is another manifestation in the film of lives which have gone beyond the boundaries of propriety and are effectively out of control. Grossing almost $400 million at the box office, this represented Scorsese’s most financially successful film to date. At a running time of almost three hours in length, this was quite a haul for a film that was mired in more than a little controversy. The director has indeed sparked some debate during the course of his career. This is one of the facets of his film-making that is so exciting as far as I’m concerned. His storytelling penchant is to present matters as they are for us the viewer to interpret. There is much respect here for the audience – Scorsese challenges us to decide for ourselves as regards characters such as Belfort. We are empowered in this regard. The great director never takes us for granted nor does he attempt to impose a certain viewpoint on us.