‘If they move, kill ’em!’ – 50 Years of The Wild Bunch

Released in the early Summer of 1969, Sam Peckinpah’s classic The Wild Bunch still feels like a brilliant anomaly in the Western genre as a whole some 50 years later. There had never been a frontier story quite like it before and no Western film ever since has managed to match its power and raw intensity. Set in 1913, the film tells the story of a somewhat disparate group of outlaws (the titular Wild Bunch) who have effectively lived past their times and have run out of options and places to go. Originally pitched to Peckinpah on the set of his ill-fated Major Dundee (1965) by a stuntman by the name of Roy N. Sickner, this is a morality play with a distinct lack of morals. Co-screenwriter Walon Green (whose pivotal decision it was to set the story in the 1910s as opposed to the 1870s) later remarked that ‘I wrote it, thinking that I would like to see a Western that was as mean and ugly and brutal as the times, and the only nobility in men was their dedication to each other.’ Indeed, this very central theme is evident from the opening credits of the film as the gang of outlaws ride into a Texan town to rob a railroad office containing a cache of silver. The arresting image of a scorpion being overrun by a plethora of fire ants is heavily symbolic and presages much of what is to come in the film’s narrative: the essential point here is that of one virulent force consuming another in an ever-ending battle to survive. The wild west incarnate you would think, but something that smacks of an even more unsparing nature.

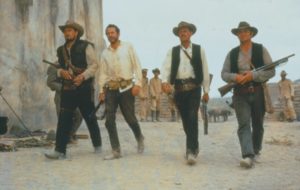

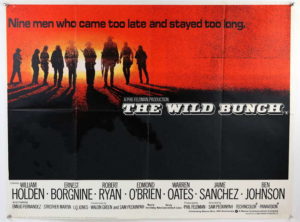

The casting of the film is one of its several remarkable features and it’s pretty much impossible to identify a weak link among the principal players. As the leader of the group, William Holden excels as Pike Bishop and it’s interesting to note that Lee Marvin – who was originally penciled in for the part – departed the project citing the fears of typecasting (following his similar role in 1966’s The Professionals) and after his agent had acquired for him a more lucrative deal on 1969’s Paint Your Wagon. For Holden, whose career had faltered badly since its peak in the 1950s, the part of Pike Bishop was an absolute godsend and he found himself in the company of a wonderful supporting cast which included Ernest Borgnine (Dutch), Robert Ryan (Deke Thornton), Edmond O’Brien (Freddie Sykes), Warren Oates (Lyle Gorch), Ben Johnson (Tector Gorch) and Jaime Sanchez (Angel). For good measure, the roles of General Mapache and Don Jose were played by prominent Mexican film directors Emilio Fernandez and Chano Urueta respectively. The idea of the opening scene – as referenced above – was purportedly suggested to Peckinpah by Fernandez. Ernest Borginine, for his part, performed a modicum of heroics on the set as he completed the film with a broken foot. The similarities between Edmond O’Brien’s Sykes and Walter Huston’s character in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre are indeed noticeable if one looks closely enough; it should come as no great surprise that the 1948 classic starring Humphrey Bogart was one of Peckinpah’s favourite films.

Peckinpah was certainly influenced by 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde and, by all accounts, he was determined to outdo the climactic sequence of the Arthur Penn film with respect to the level of graphic violence presented and the cathartic effect he hoped this might have on the audience. The so-called balletic ballistics of the film are well-known to many a cinema fan and a host of directors, including Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, Steven Spielberg and Kathryn Bigelow, have mentioned the revisionist Western as an important influence on their own work. Quentin Tarantino has described the film’s infamous shoot-out (The Battle of Bloody Porch as the cast and crew came to call it) as ‘a masterpiece beyond compare’ and there’s no doubting the intrinsic power and enduring legacy of this climactic sequence. The film’s producer Phil Feldman summed it up well when he later remarked that ‘what Peckinpah wanted to show, basically, was that dying was not glorious and people getting shot was not heroic. And he brought that quality to the picture.’ The war in Vietnam was still raging as principal photography took place and the year 1968 was notable for the civil divisions observable in American society, as well as the spate of political assassinations which occurred during that troubled time. The in-fighting which takes place among the group at several moments during the film, and their decision to sacrifice one of their own to the despicable General Mapache, is symptomatic of such strife and division. When the remaining members of the gang seek to right this inherent wrong towards the film’s end, the result is a bloody atrocity which spells their own demise, as well as many others. A sudden moral code in a world as devoid of morality as this one is a very dangerous thing we are told. An act of conscience has far-reaching implications; a belated heroic gesture holds little sway in a place and time where life is inherently cheap.

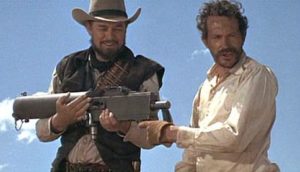

The advances in technology and the group’s outdated mode of living is a theme which Peckinpah returns to time and time again. Walon Green’s decision to set the film in 1913 was a pivotal one in this respect and the premise of ageing men who are out of sync with this ever-changing era is a stark one acknowledged even by Pike himself – ‘We’ve got to start thinking beyond our guns. Those days are closing fast.’ The decision by the gang to steal a weapons shipment from a U.S. Army train for the sinister General Mapache is an attempt of course to stage one last job before backing off forever, but it also serves to emphasise the horrific advances in the technology of modern-day warfare. Peckinpah’s overriding intention in this respect was to invent a new vocabulary for violence in cinema; to highlight its dreadful consequences and to posit the idea that surely there must be another way, one less blood-stained at the very least. The director later said that his idea was to deal with the matter of violence ‘in terms of very sad poetry’; not to praise the folly of such actions, but rather to place them firmly in the context of the utter futility of murder and mayhem. When contemporary audiences of the day reacted with a notable degree of glee to this hyper-depiction of violence, Peckinpah was said to be personally shocked. In truth, he hadn’t counted on the blood-lust of some of the audiences. 50 years later, I wonder what he would make of modern-day cinema and its sometime cartoon-like presentation of killing. I suspect he might not be so greatly surprised given the response received way back in 1969.

Contemporary reaction to the film was mixed and much critical attention focused on the stark depiction of violence which was a central feature of Peckinpah’s overall artistic design. As The New York Times’s Vincent Canby correctly predicted at the time, a great many critics and viewers dismissed the film on the basis of its graphic content. The famous ‘Agua Verde’ gun battle sequence towards the film’s conclusion (which utilised real-time and slow motion images, multi-angles and rapid-fire editing) elicited the most criticism unsurprisingly and – to this very day – it remains one of the most arresting and visually stunning montages in cinema history. In the words of the late great Roger Ebert, Sam Peckinpah preferred ‘bold images to small points.’ Writing retrospectively about the film in 2002, the famed film critic made the telling point that The Wild Bunch was incorrectly read by many in its day as a ‘celebration of compulsive, mindless violence.’ It is most certainly not that, rather a meditation on the end of an era and the men who must necessarily pass on so that a country and society can advance. Just like John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards in John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), here are individuals who have to be left behind as almost relics of the past so that civilisation may ensue. The modern world as presented in Peckinpah’s film (with its noisy automobiles and deadly machine guns) has no place for such a group as this. They are swept aside because they are obsolete by its standards and no longer present a tangible value.

50 years later, The Wild Bunch’s legacy as a great Western and – for that matter – a truly great American film is beyond dispute and it’s a testament to the work of the likes of Peckinpah, Holden and the other principal players, Walon Green, Jerry Fielding (composer), Lucien Ballard (director of photography) and Lou Lombardo (editor) – to mention but a few – that it has endured so well. Ranked by the American Film Institute (AFI) as the sixth greatest Western of all time, The Wild Bunch is, as I suggested earlier, something of an anomaly in the genre as a whole when one considers aspects of it such as the sheer brutality and honesty of its vision and the oft-ambivalent characters who populate its narrative. But what a brilliant anomaly it is and how lucky we are that it was made by individuals, such as Peckinpah, who were as uncompromising as the titular Wild Bunch themselves. To coin a phrase of Edmond O’Brien’s Freddie Sykes, it certainly ain’t like it used to be, but it’ll do. Much more than do.