In Praise Of The Bard: Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary

April 23rd, 2016 marks the 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare, undoubtedly the most famous and one of the most prolific playwrights the world has ever seen. His body of work, most especially his plays, have inspired many adaptations and re-imaginings over the years particularly in the field of cinema. According to the Guinness Book of Records (as of 2016), the number of Shakespearian adaptations stands at 410 approximately in terms of film and TV versions produced. This makes Shakespeare the most filmed author in any language. Quite a claim to fame in its own right. There are many adaptations and re-imaginings of some of his key works, and it’s not possible, or even practical, to view them all. But below are twelve I’ve selected which, hopefully, provides a useful cross-section for anyone intending to approach the Bard’s work as interpreted on the silver screen. Two of my entries are loosely based on Shakespearian plot premises; one is an amalgamation of a number of them. You may not agree with all my selections, and rail against me for some of the ones I’ve omitted, but check out one or two of the titles at least and I’m sure you’ll derive some fine entertainment, as well as encountering many classic dramatis personae. So here’s to the Bard and the next 100 years of cinema adapting and tailoring his great body of work.

Henry V (Laurence Olivier 1944)

Terrific Technicolor version of the play with Laurence Olivier multi-tasking as star, producer, director, and one of those who adapted it for the screen, this is also widely regarded as the first Shakespearian film to be successful in artistic and monetary terms. Interesting to note the particular moment when this one was made (as war raged in Europe), and the fact that Winston Churchill apparently instructed Olivier to produce an interpretation that would be morale-boosting. Compare this then to Kenneth Branagh’s later adaptation which has quite different points to make on the so-called glory of war. Shot on location at Powerscourt in County Wicklow incidentally. Hundreds of locals were hired as extras for the climatic Agincourt battle scene and paid a pound more in salary if they provided their own horse. How times have changed with the advent of CGI!

A Double Life (George Cukor 1947)

Ok, this is a bit of a stretch I will grant you, but bear with me. The great Ronald Colman plays Anthony John, a renowned stage actor who begins to blur the lines between his latest work treading the boards and his tumultuous life in the real world. He’s playing the titular role in a production of Othello and, just to further complicate matters, his estranged wife is taking on the role of Desdemona. Add to this a proclivity towards jealous rages, which has been to the detriment of his personal relationships in the past, and the similarities between him and the Moor of Venice surface only too readily with murderous consequences. Colman deservedly won the Best Actor Oscar for his performance as a man gradually losing his sanity in the full glare of the spotlight. The Bard himself I’m sure would have approved of the play-within-the-play subtext.

Hamlet (Laurence Olivier 1948)

Winner of the Best Film Oscar and also notable since Olivier is the only actor to have won an Oscar (Best Actor in this case) for a Shakespearian role, this one has been nonetheless the subject of some criticism as Olivier excised much from the original play and omitted characters such as Fortinbras, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. That having been said, it’s a terrifically atmospheric piece that still stands up as one of the best cinematic versions of what is – perhaps – Shakespeare’s most famous play. Olivier emphasises the psychological nature of the titular character’s inner torment from the get-go (‘This is the tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind’) and follows it through with Oedipal allusions and expressionistic cinematography. Notables among the cast include Basil Sydney, Jean Simmons, Christopher Lee, Anthony Quayle, Stanley Holloway and Peter Cushing.

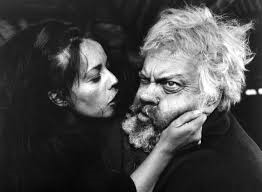

Othello (Orson Welles 1952)

Orson Welles could never be accused of being boring, or of doing things by the book, and so it goes with his film version of the Moor of Venice. The wunderkind was forced to shoot this one over a three-year period owing to the bankruptcy of the original producer and general dearth of funds otherwise. Welles poured his own finances into the production and used money earned from roles he took in films such as The Third Man and The Black Rose. This had several drawbacks of course, not the least that many sequences had to be re-shot and some parts even re-cast. But like Olivier’s Hamlet, it’s not short on atmosphere and Welles’ Othello is a suitably brooding iteration of the character. Winner of the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, three versions of this film have been released – two as supervised by Welles himself, and a 1992 restoration supervised by his daughter Beatrice Welles.

Julius Caesar (Joseph L. Mankiewicz 1953)

Excellent adaptation of the Roman history play by Mankiewicz that has Marlon Brando in the role of Mark Antony and James Mason as Brutus. Brando was on an absolute roll at this point in his career (having already made A Streetcar Named Desire and Viva Zapata!), but more than a few eyebrows must have been raised when he was cast in this production. Word has it that John Gielgud (who plays Cassius in this version, and had previously inhabited the role of Mark Antony at the Old Vic) gave him a helping hand with much of the Bard’s dialogue and inflection. It’s a terrifically marvellous performance which garnered the young actor yet another Oscar nomination for Best Actor. Antony’s funeral oration – as in the play – is a particular standout. Many sets which feature in this one were recycled from another Hollywood Roman tale, namely, Quo Vadis.

Forbidden Planet (Fred McLeod Wilcox 1956)

Even more of a stretch than the above A Double Life you will say, but consider the similarities in the plot of this science fiction classic and The Tempest. The isolated planet Altair IV in this one is the same island Prospero has been stranded on for 12 years. Dr. Edward Morbius (Walter Pidgeon) is the Prospero-type character, a scientist who, along with his daughter Altaira (Anne Francis), are the sole survivors of an expedition from earth some 20 years before. Like the magician Prospero, Morbius has learnt how to utilise his new environment’s particular forces – to often devastating effect – a fact he brings to the attention of the starship commanded by John Adams (Leslie Nielsen) at an early point in the film. His mechanical assistant Robby the Robot is a stand-in for the character of Ariel; the long-extinct, but still resonant, race of the Krell are a replacement for Sycorax; Morbius’s ‘monster from the id’ is a representation of Caliban. Notable for having been an inspiration for the Star Trek series, which it pre-dated by 10 years. I wonder what Shakespeare would have made of interstellar travel or Anne Francis’s mini-skirt. They didn’t have concepts such as those at the time of the Globe Theatre.

Throne of Blood (Akira Kurosawa 1957)

Feudal Japan is the setting for Kurosawa’s interpretation of Macbeth which is notable for, amongst other things, its employment of the setting of Mount Fuji for the castle exteriors. Regular Kurosawa collaborator Toshiro Mifune plays the role of the disaffected general (Taketoki Washizu) in this and Isuzu Yamada inhabits the equivalent of the guilt-plagued Lady Macbeth (Lady Asaji Washizu). The scene in which Washizu’s troops turn on their leader and fire a barrage of arrows at him is a particularly famous one. The scene was performed with real arrows fired by choreographed archers. There were no flashy special effects or CGI available to filmmakers back in those days and Mifune’s facial reaction to the onslaught was for real. The Bard himself, I think, would have approved of such verisimilitude.

Chimes at Midnight (Orson Welles 1966)

Welles had a keen interest in Sir John Falstaff and this one centres on that particular character and his close relationship with Henry V. Chimes at Midnight is essentially an amalgamation of text from five plays by the Bard – Henry IV Part 1, Henry IV Part 2, Henry V, Richard II, and The Merry Wives of Windsor. In true Orson fashion it was a production not bereft of delays and its own internal drama. The director struggled, as always, to get backing for the film and eventually resorted to a lie when convincing producer Emiliano Pedra that he would make a version of Treasure Island. The condition agreed on was that filming of both stories would occur simultaneously. Welles, of course, did not live up to his end of the bargain, but managed somehow to get away with the ruse. He also managed some other deft tricks on set such as shooting the Battle of Shrewsbury sequence with a mere 180 extras, but making it appear as if thousands were employed. The result of all this is a film (only recently returned to general circulation mind) which Welles described as his favourite picture and his most personal one along with The Magnificent Ambersons. He subsequently said that if he wanted to get into heaven on the basis of one movie alone, then this was the one he’d offer up. High praise for his own work indeed. I wonder if Shakespeare would agree with him on this. I’m sure he’d have an opinion.

Ran (Akira Kurosawa 1985)

Akira Kurosawa takes us back to feudal Japan for his re-imagining of King Lear, perhaps Shakespeare’s bleakest tragedy of all. In this version the Lear character, Hidetora, is a powerful warlord who, having spent most of his life consolidating his dominion through conflict and bloodshed, decides to abdicate in favour of his three sons (as opposed to three daughters as in Lear). The proposed division of his kingdom is not accepted by all of course and Hidetora banishes his youngest son Saburo for speaking the truth. Hidetora soon finds that there is little prestige in his abdication and, following his refusal to give up his title as Great Lord, is estranged from his other two sons and left only with his retinue, concubines and Kyoami (the Fool in this adaptation). This is generally recognised as Kurosawa’s last epic, and also one of his finest films (as a director he made three more films, concluding with 1993’s Madadayo). It was also the most expensive film produced in Japan up to that time, and Kurosawa’s meticulous preparation for it (he co-designed uniforms and suits of armour, and painted storyboards for every shot in the film) is all up on the screen. The film was nominated for Oscars for Best Director, Art Direction, Cinematography and Costume Design; and won for Costume Design. Scandalously, it was not submitted that year as Japan’s entry for Best Foreign Language Film owing to some bad feeling between Kurosawa and the upper echelons of the Japanese film industry. American director Sidney Lumet subsequently led a successful campaign to have Kurosawa nominated in the Best Director category. The nomination was well deserved.

Henry V (Kenneth Branagh 1989)

Kenneth Branagh was still in his 20s when he made this one – his directorial debut no less as well – but he handled it with great aplomb and delivered one of the finest Shakespearian adaptations in the process. Well worth comparing it with Olivier’s earlier version (as referenced above), this one is noteworthy in terms of its far less glorified depiction of war (remember how jingoism was a factor in the production of Olivier’s film), most especially in relation to the Battle of Agincourt set-piece (rain-drenched mud as opposed to sun-lit pastures). Elsewhere there’s a lot more to admire in a stellar cast – including Paul Scofield, Emma Thomspon, Robbie Coltrane, Judi Dench and a young Christian Bale – and a fine score by then first-timer Patrick Doyle. And, of course, the stirring St. Crispin’s speech which is performed with great gusto by the young Northern Irish actor himself, on his way to a Best Actor Oscar nomination. He also received a nomination for Best Director and Phyllis Dalton won for Best Costume Design.

Hamlet (Kenneth Branagh 1996)

Kenneth Branagh’s unabridged theatrical version of the play has a running time of four hours and updates the setting to the 19th century. It’s probably not possible to watch this in one sitting, but it certainly is worth persevering with and I, for one, would suggest a game of two halves. This adaptation is especially noteworthy in that it employs flashbacks of scenes which are often only described or implied in the original play. Branagh also chooses a very singular visual approach with vibrant colours and opulent interiors, causing one critic to declare the overall effect, ‘film noir with all the lights on.’ The ensemble cast is huge and even bit parts are populated by very well-known faces. Julie Christie plays Queen Gertrude. Kate Winslet is Ophelia. The lead role needs no introduction.

Macbeth (Justin Kurzel 2015)

And lastly this one, and it’s a very recent entry at that. Justin Kurzel’s adaptation of one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies remains quite faithful to the source material, whilst employing a very distinctive cinematic style of its own. The film also benefits in particular from a towering central performance by Michael Fassbender as the Thane with blood on his hands, and he’s well supported by Marion Cotillard as Lady Macbeth and others, including Paddy Considine and Sean Harris. The film competed for the Palme d’Or at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, where it also had its world premiere.

I’d forgotten about A Double LIfe so thank you for the timely reminder! Personally I much prefer Mel Gibson’s Hamlet to Mr Branagh’s – c’est la guerre. Good catchup!

Yes, A Double Life is a fine film, with a great central performance from the peerless Ronald Colman. Gibson’s Hamlet left me sort of cold to be honest.