‘Madness! Madness!’ – 60 Years of The Bridge on the River Kwai

The theme of all-consuming duty and devotion to a cause is a central one to David Lean’s 1957 epic war film The Bridge on the River Kwai which celebrates the 60th anniversary of its release in October 2017. Based on the 1952 novel Le Pont de la Riviere Kwai by French novelist Pierre Boulle (Planet of the Apes), the film relates the story of a group of World War II prisoners who are compelled to construct a railway bridge over the titular River Kwai by their Japanese captors. The intended structure is of strategic value to the Japanese war effort as it will connect Bangkok and Rangoon and the commandant, Colonel Saito (Sessue Hayakawa) realises the personal cost to himself and others if the sizable undertaking is not completed on time. In this task, however, he soon comes face to face with a seemingly worthy adversary in the guise of the senior British officer Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson – as played by Alec Guinness in an Oscar-winning performance.

The inhospitable environs of the jungle setting are perfectly captured by David Lean and his director of photography Jack Hildyard in Kwai’s opening scenes. A train bearing prisoners of war stops along the tracks of an incomplete railway line amidst dense forest and tangled vegetation. We see numerous grave markings as the captive troops are led into their place of internment – most viewers will remember this scene for its employment of the well-known Colonel Bogey March. It’s an early nod to national pride and jingoism which is surely misplaced in such an unwelcoming location. Nicholson himself seems to avert his eyes as he spots worn out shoes and threadbare clothes in the searing heat. Watching close by is an American commander (so-called) by the name of Shears (William Holden). He scoffs as he watches this rather empty military display – and for a very good reason. Shears is only too well aware of the harsh conditions of the camp and the inflexible rule of the aforementioned Saito. He has just dug a grave for an ‘English kid’ – not his first – and concludes his blunt oration hoping that the deceased soldier will, ‘rest in peace. He found little enough of it while he was alive.’

Nicholson is somewhat taken aback when informed that Saito expects officers to work alongside enlisted men in the construction of the bridge, but is quite sure he can talk sense into his counterpart. When he first meets Shears, Nicholson – rather naively – describes the Japanese Colonel as appearing to be a ‘reasonable’ man. The ever-cynical Shears confides the truth of the matter to the British medical officer Major Clipton (James Donald) – ‘I can think of a lot of things to call Saito, but ‘reasonable’, that’s a new one.’ The performance of Holden throughout Kwai is very reminiscent of his turn in 1953’s Stalag 17 which had earned the American the Academy Award for Best Actor. The earlier Billy Wilder prisoner of war film was surely a major factor in Holden’s casting in Kwai. The David Lean epic benefits generally from its fine cast which includes other notables such as Jack Hawkins, Andre Morell and Geoffrey Horne. Holden and Guinness are at the top of their games in their respective roles. Sessue Hayakawa who, incidentally, was one of the biggest stars in Hollywood during the silent era of the 1910s and 1920s, received an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor in a Supporting Role.

Saito’s inflexibility becomes all too apparent to Nicholson as the former continues to insist that officers should engage in manual labour. After he has been physically reprimanded by Saito, Nicholson is threatened with a show of force – a machine gun on the back of a truck. He refuses to yield in the baking heat and is beaten and subsequently placed in the ‘oven’ as Shears calls it (he also caustically remarks on the, ‘kind of guts that can get us all killed’). That very same night, Shears and two others – an Australian and a recent British internee – attempt to escape their jungle prison. The Australian and Englishman are shot and killed as they try to flee; Shears, for his part, is wounded, but manages to swim away. Three days later, the level-headed Clipton attempts to intervene in the situation as he requests medical attention for Nicholson, who is still holed up in the ‘oven.’ The pressures coming to bear on Saito are well expressed in this scene as the latter bemoans the lack of progress on the bridge. Morale among the troops is at a low and acts of sabotage are rampant; the implications for Saito personally are quite clear – if the project is not delivered within the set time period, then he must literally fall on his own sword (‘Do not speak to me of rules! This is war!). But the dogged Nicholson is equally as steadfast and emphatic in his position – ‘It’s a matter of principle,’ he tells Clipton as he vows to remain in the ‘oven’ until Saito exempts the officers from manual duties – ‘Here is where we must win through.’

Saito’s decisions to declare a temporary amnesty in good faith and to take personal charge of construction do not have the desired effect and he is reduced to pleading with Nicholson for some form of compromise on his part. Nicholson refuses to agree to Saito’s terms (only junior officers to be required to work) and is once again returned to the constricted space that is the ‘oven.’ Finally defeated, Saito uses the occasion of the anniversary of Japan’s victory over Russia in 1905 to completely excuse British officers from manual labour; in private, he weeps bitterly out of a sense of shame. The released Nicholson on the other hand is hailed as a hero by his men. A creeping sense of obsession is soon established in the film as Nicholson determines to build the bridge to the best possible specifications and within the time that has been allotted. ‘It’s going to be a proper bridge,’ he declares as he sees in this project an opportunity to rebuild the battalion itself and, consequently, the morale of his men. In a subsequent meeting involving his officers and Saito, Nicholson advises of the need to re-locate the position of the bridge to a spot further upriver where the bedrock is more sustainable. Even Saito himself appears surprised by Nicholson’s zeal and drive apropos the enterprise.

In the meantime Shears has found his way back to civilisation and is currently living it up at the Mount Lavinia Hospital in Ceylon. An unexpected visit by a Major Warden (Jack Hawkins) proves an unwanted distraction in this regard, but Shears agrees to provide some information on the bridge which is being constructed in the jungle. ‘He had the guts of a maniac,’ he observes with reference to Nicholson as he learns of the planned mission to destroy the bridge in question; he is also not best-pleased by Warden’s request that he accompany him and his team of commandos on this dangerous assignment. Admitting that he is neither a commander or an officer (he had swapped uniform with a dead man), Shears reluctantly agrees to assist Warden and his team. The objective is clear-cut – destroy the bridge before it becomes fully operational; obliterate it entirely so that it can never serve to bolster the Japanese war machine. ‘As long as I’m hooked, I might as well volunteer,’ a resigned Shears comments as he consents to go on the expedition.

We are provided with further evidence of Nicholson’s obsessive streak as work on the bridge gathers pace and exceeds all expectations. Dismissing Clipton’s concerns that their efforts might be considered an act of collaboration, Nicholson once again remarks on the importance of the task from a uniquely British point of view – this is a structure which he is convinced will stand long after all of them have shuffled off their mortal coils. This will be a testament to British engineering and general know-how; this will be their moral victory in this most desolate of places. To this purpose, the Lieutenant Colonel entreats his own officers and the sick among his men to assist in one last push to complete the bridge on time. Gone now entirely are his previous high-minded principles concerning officers being exempt from such work. Again, the increasingly mute Saito is amazed as he witnesses Nicholson leading the sick and wounded to the construction site.

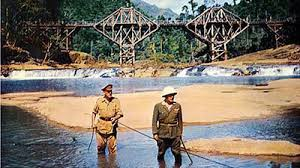

A similar form of single-mindedness and fixation becomes manifest in the parallel story as Warden leads his team (consisting of Shears, a young Canadian lieutenant by the name of Joyce (Geoffrey Horne) and their Siamese women carriers) through the jungle and in the direction of the near-completed bridge. Wounded in an exchange with an enemy soldier, Warden stoically insists on proceeding as planned. The lure of destroying the structure on the occasion of its opening ceremony proves irresistible to him and he is berated by Shears for his own lack of self-preservation in this regard – ‘Crazy with courage,’ the American remarks as he likens this compulsive behavior to that of Nicholson’s. With more than a tinge of unwillingness, Warden finally agrees to be borne on stretcher by the Siamese carriers. The masterful shot in which Warden and the others first see the bridge is certainly one of the most memorable of the film. The major, for his part, opines on how well it appears to be constructed; down below, meantime, a suitably proud Nicholson surveys the finished job. A plaque adorning the completed bridge informs of how it was, ‘designed and built by soldiers of the British army.’

Fixing upon a plan for the destruction of this effort by those same soldiers of the British army, Warden decides that the cover of darkness will provide Joyce and Shears with the opportunity to plant explosives along the towers. There is a remarkably tense scene which occurs as a sentry paces the bridge whilst the two men work silently below. The Oscar-winning score by Malcolm Arnold (which the British composer wrote in a very short space of time) is not employed in this sequence and, instead, we listen to the attendant sounds of the flowing river and rustling jungle. In the far distance can be heard a variety show as Nicholson and his men celebrate their ambiguous achievement; however, there is no such note of ambiguity as Nicholson addresses his underlings – ‘You have survived with honour,’ he tells them with no small amount of satisfaction, ‘You have turned defeat into victory.’ As Shears and Joyce complete their work in the darkened river, Nicholson and his men burst into a rousing rendition of God Save the King. The following morning, however, and much to their horror, the river has gone down revealing the wire which connects the charges to the detonator. ‘Don’t wait for the train! Do it now!’ Warden whispers to himself as he wills Joyce on to trigger the mechanism. As the approaching locomotive is heard in the distance, Nicholson, who the night before had been reminiscing about his career in the service (‘Tomorrow it will be 28 years to the day that I’ve been in the service. 28 years in peace and war. I don’t suppose I’ve been at home more than 10 months in all that time’), discerns the wire and begins to suspect that something is very much amiss. Alerting Saito to this, he checks along the bank of the river and discovers that there is a plan afoot to destroy his beloved bridge. ‘He’s gone mad!’ Warden surmises from his position, ‘he’s leading him right to it! Our own man!’ The viewer too is forced to question Nicholson’s motivation at this point. Surely, this is the culmination of misplaced pride and honour. Has Nicholson forgotten who and what he is? Has he entirely abandoned his allegiances? Joyce kills Saito, but the torn Nicholson tries to prevent him from activating the detonator. A visibly incensed Shears crosses the shallow river, but is shot by the Japanese, as is Joyce. One of the most memorable scenes in Kwai is the final encounter which takes place between Nicholson and Shears. The Lieutenant Colonel has assumed all this time that the American is dead; when he recognises him, he also realises the level of sacrifice and duty Shears has exhibited in returning to this forsaken place. As Shears lies dead in the water, Nicholson’s sense of loyalty finally returns (‘What have I done?!’) and he determines to complete the task of Joyce and Shears. Though fatally wounded himself, Nicholson manages to drag himself to the detonator. In one last final gasp, he falls upon the device. An iconic moment in cinematic history unfolds as the bridge is utterly destroyed in the ensuing explosion. From a close vantage point, a watching Clipton sums up the lingering feeling which is prevalent in the viewer’s mind – ‘Madness! Madness!’ The madness in question is one which is a familiar theme of such films I would suggest – the sheer futility of war. And the questionable acts and courses it causes men such as Nicholson to pursue in spite of their better judgement.

The Bridge on the River Kwai deserves its place in the list of great war movies by reason of its epic quality, the superb production in general, the direction of Lean, cinematography of Hildyard, the terrific performances of its cast and the underlying themes which it so effectively explores. With regard to the screenplay by Carl Foreman (High Noon, The Guns of Navarone) and Michael Wilson (A Place in the Sun, Planet of the Apes), it is interesting to note how both these writers were on the Hollywood blacklist at the time and could only work on the adapted script in secret. Pierre Boulle – who’d himself been an Allied POW during the war – was credited with the resulting work and, subsequently, awarded the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay. This travesty of justice was eventually rectified in 1984 when Foreman and Wilson were posthumously recognised by the Academy for their work. In all, Kwai won seven Oscars at the 30th Academy Awards ceremony held on the 26th March, 1958 – Best Motion Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Original Score, Best Cinematography and Best Film Editing. Alec Guinness later admitted that he had based the unsteady walk of his character Nicholson – when emerging from the ‘oven’ – on that of his son Matthew who was recovering from polio at the time. Based loosely on the construction of the Burma Railway between 1942 and 1943, Kwai is a war film which focuses on private individuals more so than larger events; it puts their various codes and motivations on display for the viewer and asks us who we think is right in such a vacillating moral universe. The madness of the piece – as so tersely expressed by Clipton – is that war is ultimately a pointless exercise which forces essentially good men down paths they would not otherwise think to traverse. Happily, the path taken by David Lean himself in accepting directorial duties on this particular film led on to other memorable epics such as 1962’s Lawrence of Arabia, 1965’s Doctor Zhivago, the underrated Ryan’s Daughter of 1970 and his final film in 1984 – A Passage to India. Kwai marks an important watershed for Lean the director delineating, as it does, the two halves of his career – the smaller and more intimate films from 1942 to 1955 (which include his peerless adaptations of Great Expectations and Oliver Twist, as well as Blithe Spirit and Brief Encounter) and the much broader works from 1957 onwards with which he is so often associated. 60 years on since its initial theatrical release, Kwai continues to enjoy its fine legacy and has been deservedly recognised by cinematic bodies such as the American Film Institute and the United States National Film Registry. There is no madness in any of this. Six decades later and the epic war film more than stands up to repeated viewing. A classic from one of the undoubted masters of epic cinema.