Movie Retrospective: Il Vangelo Secondo Matteo (The Gospel According to Matthew)

There’s little doubt about the fact that 1950s and 1960s cinema proved to be fertile ground for the biblical epic. Titles such as Henry Koster’s 1953 The Robe and DeMille’s 1956 The Ten Commandments spring readily to mind. Charlton Heston and Stephen Boyd went head-to-head in a famous chariot race in William Wyler’s 1959 remake of Ben-Hur. Elsewhere, Jeffrey Hunter played the part of Christ in Nicholas Ray’s 1961 King of Kings. Four years later, Ingmar Bergman regular Max von Sydow played the Messiah in George Stevens’ rather overblown The Greatest Story Ever Told. Released just a year before that latter film, in 1964, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s quite extraordinary Il Vangelo Secondo Matteo fully deserves its reputation as the greatest film ever made about Christ. Dedicated to the memory of Pope John XXIII (who’d passed away in 1963), it’s easy to understand why Pasolini, a self-regarded Marxist poet and intellectual more than a film director, chose to do so given that that particular papacy had advocated a new dialogue with non-Catholic artists. Pasolini was an avowed atheist who in his own words did not believe that Christ was the son of God ‘because I am not a believer – at least not consciously. But I believe that Christ is divine: I believe, that is, that in him humanity is lofty, strict and ideal as to exceed the common terms of humanity.’

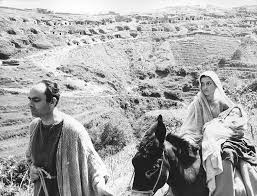

The opening of Il Vangelo is sparse with respect to its dialogue and minimalist in terms of the grandeur of the subject matter. Reverse shots bereft of verbal communication occur between Joseph and Mary. The former has just discovered that she is with child as a result of the Immaculate Conception. Struggling to understand this, and despairing as to what the future holds, Joseph temporarily abandons her and lies down close to where a group of children are playing. He awakens to the vision of an angel who informs him of the role he must play in Jesus’s birth and upbringing. Rushing back to his intended, Joseph’s new-found strength and purpose is again conveyed by tight reverse shots. Throughout the duration of Il Vangelo, Pasolini uses such framing in order to draw us the viewer into this world. Beginning as it does prior to the Nativity and ending following the resurrection, Il Vangelo is intentionally devoid of the visual and narrative embellishments which Hollywood films of the day employed when telling this story. Consider for example the fact that there is no shot of the Star of Bethlehem in the film, a traditional motif which appears in films such as Ben-Hur. Il Vangelo is instead noteworthy for its use of locations in Southern Italy such as Basilicata, Puglia and Calabria. The region of Lazio doubles for Galilee. Pasolini had originally intended to shoot Il Vangelo in Palestine and indeed scouted there for suitable locations; however, he was disappointed to discover that modern-day Palestine had become heavily industrialised and was no longer fit for purpose.

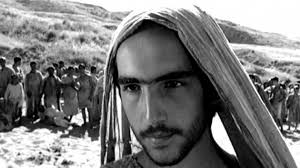

Il Vangelo is shot through with a very definite neorealist style and this extends to the cast itself which, for the most part, was non-professional. Much of the film, therefore, has a very authentic feel about it – cinema verite in its very finest form. Enrique Irazoqui, who portrays Jesus, was then a 19-year-old Spanish student who had sought Pasolini out for an interview. The director interrupted the student’s questions by asking him if he would be interested in acting in one of his films. Irazoqui initially declined, but was eventually won over to the idea. Pasolini stated that he was drawn to the idea of Irazoqui playing Christ given his physical resemblance to the depiction of the holy one in El Greco’s 1579 painting The Disrobing of Christ. Of note among the cast as well is Pasolini’s mother Susanna who plays the elderly Mary.

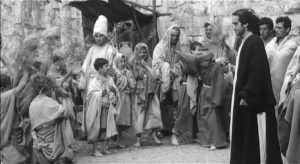

Il Vangelo does not follow the traditional style of other biblical epics in many other ways as well. There are no major set-pieces with respect to the crucifixion or such seminal events as the miracle of the loaves and fishes. The Jesus portrayed here is as per the text of Matthew, one who has not come to bring peace, but a sword. As he embarks upon his public life, Pasolini isolates him in a succession of shots whereby he is – presumably – speaking to the masses who have come to see him. But there are no wide shots of such crowds; not a sign of budgetary constraint in this instance, but rather a deliberate decision by the director himself. Pasolini stated that his intention was to portray Christ as an ambiguous figure and such is the case as he challenges the authorities and the very institutions they represent. The text of Matthew commonly has a Christ who is on the offensive in terms of his language and who answers a question with a question. In one particular scene Irazoqui is surrounded by some adoring children whom he smiles upon genially before turning the wrath of his words on the Jewish high priests. Christ is at once an embodiment of kindness juxtaposed with his more politically-charged and highly articulate alter ego. The effect is continued at his trial which is done in long shot and from a third-person perspective. The director of photography of Il Vangelo, Tonino Delli Colli, should be well known to many a Sergio Leone fan; the Rome-born DOP served duties on some of the director’s greatest works including The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Once Upon a Time in the West and Once Upon a Time in America.

Of even greater significance to the film as a whole was the director’s prior decision to use the Gospel of Matthew essentially as the shooting script. Pasolini said he decided against the other Gospels because he felt ‘John was too mystical, Mark too vulgar and Luke too sentimental.’ With respect to The Gospel According To Matthew, Pasolini subsequently went on the record to say that his narrative device was to follow the text ‘point to point, without making a script or adaptation of it. To translate it faithfully into images, following its story without any omissions or additions. The dialogue too should be strictly that of Matthew, without even a single explanatory or connecting sentence because no image or inserted word could ever attain the poetic heights of the text.’ The director expressed his own dissatisfaction a few years later by the decision of English-speaking countries such as the UK and Ireland in re-inserting the St. before the name of Matthew in the film’s title. The powers-that-be evidently missed the point the director was making in this regard. The Christ here is divine, but he is nonetheless a mortal man who is subject to the harsh world around him. The same with the apostles who are unremarkable men and, appropriately, played by untrained actors.

One cannot discuss Il Vangelo without paying reference to its quite remarkable score, including the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, Mozart and Sergei Prokofiev. The eclectic music however gains its real distinction when one considers the inclusion of the traditional spiritual song Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child as performed by Odetta Holmes and Blind Willie Johnson’s Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground. The Jewish ceremonial declaration Kol Nidre also features, as does Gloria in excelsis Deo. Pasolini stated that his desire in this aspect of the film was to utilise musical pieces from all corners of the world and multiple cultures which had a particularly sacred or religious tone. The effect is quite resonant and commendably all-embracing.

Debuting at the September 1964 Venice Film Festival, Il Vangelo was praised by the Catholic Church, but derided by Pasolini’s fellow Marxists who believed the poet/novelist had softened his anti-religious stance, especially with regard to organised religion. The film won the Special Jury Prize at Venice and, when released in the United States in 1966, received three Oscar nominations for Best Art Direction, Best Costume Design and Best Score. The scenes towards the end of Il Vangelo as Susanna Pasolini, playing Mary, reacts in horror to Jesus’s crucifixion have their own sorrowful undercurrent if one considers the violent end which Pasolini himself met in 1975. The director’s death is still a mystery and the source of on-going conjecture. Varying theories include him being killed by an extortionist or by a number of individuals with a Southern accent who called him a dirty Communist. Whoever the perpetrators and whatever their reasons, his untimely death at the age of 53 robbed the film world of a true, if controversial, talent. In 1995, on the 100th anniversary of cinema, the Vatican unveiled its 45 great films list which was divided into three groups of Religion, Values and Art. Il Vangelo is amongst those listed under Religion. More recently – in 2015 to be precise – L’Osservatore Romano, the daily newspaper of the Vatican City State, went one step further by declaring Il Vangelo the best film on the life of Christ. These two latter accolades would probably have brought a wry smile to the face of the director were he still alive to this day. He would have seen a certain irony in such praise from the aforementioned institution and one of its media arms. And would have had something to say about it as well no doubt.