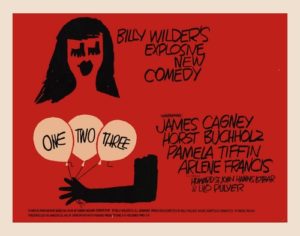

Movie Retrospective: One, Two, Three

Billy Wilder made a total of 11 comedies between 1955’s The Seven Year Itch and 1981’s Buddy Buddy (the director’s final film which featured regular acting collaborators Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau). The most famous of these are undoubtedly 1959’s Some Like It Hot and 1960’s The Apartment, but the film which directly followed these two classics – 1961’s One, Two, Three – is a comedy which deserves much overdue recognition in the Wilder canon as a whole. Featuring a tour de force central performance by the great James Cagney, and notable for its fast-paced tempo and hectic dialogue, One, Two, Three is a film which richly repays repeated viewing and is up there with the very best of the comedies of this type. That it did not perform as well as other Wilder films on its initial theatrical release should not detract from the reputation it is now due. An exemplary cast, a comically-astute script (with machine-gun rapidity) and the deft employment of Aram Khachaturian’s instantly recognisable Sabre Dance are but a few of the wonderful ingredients to savour in this side-splitting film from the Cold War era.

Wilder as we know was one of the most versatile directors of classical Hollywood and the story which he fashioned with regular writing collaborator I. A. L. Diamond fluctuates between moments of broad farce and political satire. A high-ranking executive in the Coca-Cola Company by the name of C.R. MacNamara (Cagney) is currently stationed in West Berlin where he presides over an office notable for its overly attentive staff (who stand to attention every time the boss man enters the room); the sycophantic Schlemmer (played by German actor Hanns Lothar) being the very embodiment of this throwback to a previous era. In the very best tradition of the capitalist mindset, Mac has aspirations to advance further in the company and has his eye on a lucrative position in London which, if obtained, will see him head up Western European Operations. Fate (or a recipe for disaster) intervenes when Mac receives a phone call from his boss W.P. Hazeltine (Howard St. John) requesting that he keep an eye on the latter’s daughter Scarlett (Pamela Tiffin) for the duration of her two-week stay in Berlin. The dim-witted socialite overstays her welcome in more ways than one and after several weeks Mac is horrified to learn that she has found herself a husband in the form of an impassioned young Communist by the name of Otto Piffi (German actor Horst Buchholz of The Magnificent Seven fame).

With One, Two, Three Wilder wanted to make ‘the fastest picture in the world’ and one certainly cannot fault the Oscar-winning director for taking his best crack at it. From start to finish the film moves along at a frenetic rate and is noteworthy for the speed of its dialogue which is up there with the likes of 1940’s His Girl Friday (Wilder, incidentally, made his own version of the original play on which it was based by way of 1974’s The Front Page). Upon learning of Scarlett’s hasty nupitals, and the imminent arrival of Hazeltine in Berlin, Mac attempts to deal with the unwanted problem of Otto by framing the hot-headed party member and having him picked up by the East German police. The plan appears to work when Otto cracks under the strain of interrogation (his captors repeatedly play Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini) and signs a confession to the effect that he is an American spy. But when the increasingly beleaguered Mac learns that Scarlett is pregnant by Otto, he is forced to change tack and retrieve the young father-to-be from the grips of the anti-capitalists. In the service of such a purpose, it is highly amusing to watch the sequence of events which unfolds as Mac bribes his way back into East Berlin and employs his own secretary (Liselotte Pulver) to help free Otto. A madcap car chase scene culminates at the iconic Brandenburg Gate and sets in motion the lightning momentum of the film’s final third. It’s little wonder perhaps that James Cagney did not make another film for twenty years such were the heady physical exertions demanded of him by Wilder and Diamond’s quite relentless script.

Upon their return to the relatively safe and conventional environs of West Berlin, Mac determines that his best (and only) course of action is to somehow transform Otto into the very antithesis of all that he despises – namely a devoted capitalist worker. The young man naturally balks at the thought of such an intolerable idea and his mood hardly improves as he is fitted out with expensive attire and foisted with a new name (of aristocratic pedigree). Cagney’s performance in all of this is a sheer marvel to behold and the 62-year-old clicks his fingers and delivers the dialogue with the enthusiasm and robustness of an actor half his age. It’s hardly surprising that no less than Orson Welles once said of him that he was ‘maybe the greatest actor who ever appeared in front of a camera.’ Best known to audiences for his roles in films such as The Public Enemy (1931), Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942 – for which he won the Academy Award for Best Actor) and White Heat (1949), the New York-born actor displayed an innate aptitude for comedy at this later stage of his career. The only pity was that he would go on to make just one more film (1981’s Ragtime) prior to his death in 1986. In an illustrious acting career which spanned some seven decades, this is a performance of Cagney’s which deserves reappraisal just as much as the film itself.

The other principals of the cast are superbly employed as well and particular standouts include the aforementioned Hanns Lothar as Mac’s devoted assistant Schlemmer (who has a cross-dressing moment reminiscent of Some Like It Hot), Pamela Tiffin as the simple-minded Scarlett and Arlene Francis as Phyllis, Mac’s slightly disgruntled and long-suffering wife. A special mention should also be extended to actors Leon Askin, Ralf Wolter and Peter Capell who play a trio of Soviets who Mac negotiates with (and hoodwinks) in order to secure Otto’s release. Once billed as the ‘German James Dean’, Horst Buchholz fares quite well as Otto also, although stories which emanated from the set would suggest that he and Cagney did not exactly get along during filming. The closing moments of One, Two, Three are perhaps a little less than plausible with respect to Otto’s apparent (and sudden) conversion to Western ways (he is appointed the new head of Western European Operations by his impressed new father-in-law Hazeltine), but the film appropriately closes with Cagney’s character as he discovers a Coke machine at Berlin Airport stocked with Pepsi-Cola. A bemused expression written on his face, he calls out once more for his faithful right-hand man – ‘Schlemmer!!’

A more than interesting historical occurrence took place during the course of principal photography when the Berlin Wall began construction in August 1961. The cast and crew were forced to move to Munich for the remainder of the shoot, but, thankfully, this did not impinge in any way on the quality of the resulting film. Although it did not perform well at the contemporary box office, One, Two, Three has been the subject of renewed interest and much critical praise. It may not be Wilder’s most famous film, or comedy for that matter, but it most certainly is one which merits a re-evaluation and a second if not third look. Cagney and Wilder at the very top of their respective games. More than one, two or three moments of comic brilliance to relish in this one.