Movie Retrospective: Paris, Texas

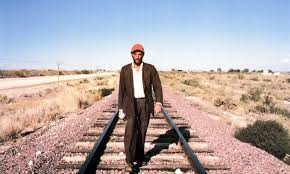

Wim Wenders’s 1984 Palme d’Or-winning film Paris, Texas opens with a solitary figure ambling unsteadily through the South Texas desert landscape. This might well be the beginning of a western in the John Ford mould as far as we the viewer are concerned, but the film’s contemporary setting is quickly established as the camera draws closer to its subject – Travis Henderson (Harry Dean Stanton). Donning a shabby baseball cap and long-worn clothes, his rugged face is like a map of the human soul itself, replete with lines and blemishes; imperfect and with a back-story which we can only speculate upon at this early time. Travis emerges from this inhospitable environment simply for the reason that his water has run out. Collapsing in a remote saloon, he is examined by a German-sounding doctor (Bernhard Wicki) who concludes that the man is a mute. A call is put through to Travis’s brother Walt who travels from his home in L.A. Walt admits that he hasn’t seen Travis in over four years and is puzzled at his brother’s withdrawn demeanour. ‘You look like 40 miles of rough road,’ he comments with regard to Travis’s appearance. When Travis attempts to return to his mysterious odyssey by leaving the motel they are staying in, Walt enquires as to what he is in search of. ‘What’s out there?’ he asks. ‘There’s nothing out there.’

Walt informs the still-speechless Travis that his seven-year-old son Hunter has been living with him and his French wife Anne ever since he and his wife Jane disappeared all those years ago. Travis finally breaks his silence when pressed by Walt uttering the single word ‘Paris.’ He shows his brother a picture of a vacant lot in Texas explaining that it is a place called Paris, Texas and that he purchased this particular lot, which he jokingly describes as ’empty,’ some time before. When quizzed by Walt as to why he would even bother to buy a vacant lot in Paris, Texas, Travis answers that he can’t remember. A planned flight back to L.A. does not work out when he insists on disembarking just prior to take-off. Walt decides the only option is to drive back and the brothers set off on one of a series of journeys which permeate the narrative. On the road Travis recalls why he purchased the vacant lot in Paris, Texas. He figures that this is the place where he was conceived – where his story began. He also reminds Walt of the joke their father used to constantly make in introducing their mother as the woman he’d met in Paris, as if it were Paris, France and not Paris, Texas.

The two men eventually arrive in L.A., but Travis’s taciturn manner continues. Politely, he refuses to reveal where he has been for the last four years and what happened between himself and Jane. Re-connecting with the son he hasn’t seen in all this time does not prove to be seamless either, especially when the young boy refuses to walk home with him one day after school. A turning point, however, comes when Walt puts on a Super 8 home movie of the two couples and Hunter shot some five years previous in Texas. Hunter begins to engage with Travis as he watches his reaction to these moving images from the past, addressing him as ‘Dad’ for the very first time. We also catch our first glimpse of Jane (Nastassja Kinski), Travis’s missing wife who is obviously much younger than her husband. The resuming bond between father and son is best exemplified perhaps in the playful scene in which Travis dresses up to look like a ‘rich father’ and walks home with Hunter after school. Mimicking his father’s gait and stride, the young boy demonstrates that he has an emotional awareness beyond his years. This will reveal itself even more so in a following scene when the two decide to journey to find the missing member of their family.

Growing anxious as to how Hunter and Travis are getting closer Anne (Aurore Clement), reveals to the latter that Jane had been calling up to a year before enquiring as to Hunter’s well-being. The calls stopped suddenly, but she lodges some money for her son on the fifth day of every month in a bank in Houston. Determining to travel there and find his seemingly estranged wife, Travis tells his plans to Hunter who insists on accompanying him. The two depart without informing Walt or Anne. They follow a car from the bank and arrive at a peep show club somewhere in the suburbs. The rather garish environment is most distinctive with respect to its private rooms which are equipped with telephones and one-way mirrors. Travis’s first attempt to speak with his wife does not go well and he leaves the room under a veil of silence and some residue of bitterness. Getting drunk that same evening, he tells Hunter the story of his parents and the place called Paris, Texas. The joke he’d previously reminded Walt about has its more doleful side with respect to the fact that Travis’s mother was a very shy and plain woman who was embarrassed whenever her husband introduced her as the ‘woman he met in Paris.’ Travis remarks on how his father practically started to believe this story himself, wanting to imagine almost that his wife was glamorous in some way, which she most certainly was not. It’s one of several moments in Wenders’s film (and the script by L.M. Kit Carson and actor-playwright Sam Shepard) in which a character attempts to construct a narrative or a concept which does not exist, which, in truth, is an impossibility. ‘This is no place to bring a fancy woman,’ the inebriated Travis declares in an indirect reference to this theme. No place is precisely no place. The vacant lot in Paris, Texas is indeed ’empty’ as he previously described it; ‘dirt’ in the succinct words of Hunter.

Travis decides to return to the peep show club, but, first, leaves a tape recording for Hunter in the hotel where they are staying. He reveals how he was the one who’d split the family apart with his rages, his drinking, and his deep-seated jealousy. He also informs the boy that he is going away on account of his past behaviour. ‘I can’t heal up what happened,’ he explains. Jane appears again in one of the club’s private rooms and Travis gradually imparts their own story to her (‘I knew these people…’). We learn the truth of what happened to their marriage; the obsessions and eventual hatred which infected it; the love that still lingers, but which is an unsustainable dream now. In the aftermath of a fire which occurred in their trailer home, Travis hints at the four-year journey he embarked upon in which he tried to entirely divorce himself from human contact and meaningful communication – ‘For the first time, he wished he were far away. Lost in a deep, vast country where nobody knew him. Somewhere without language or streets.’ He tells Jane to go to the hotel where Hunter is waiting and re-commence the proper relationship of mother and son. Jane tells Travis of how she has thought about him during the intervening years. She describes how she often hears voices and imagines that they are his. But Travis is adamant that he cannot re-join the family unit. He drives away at the film’s end having satisfied himself that Jane has gone to the hotel and reconciled with their son. A side profile of his face suggests some tears and a gentle smile. The last image is fittingly that of the road again as his car departs leaving the populous city in its wake. Travis is on a journey again, but we are uncertain as to where he is headed. Perhaps he doesn’t even know himself. It begs the question: Is this a happy ending?

I previously mentioned the theme of journeys which is one of several that informs the narrative thrust of Paris, Texas. At the film’s beginning, Travis emerges from a four-year journey which has taken him to God knows where. He never reveals the exact details of this, but his subsequent conversation with Jane hints at the isolation and solitude which he has sought out. Then there is the journey involving him and his brother; followed by that of father and son. The final journey is shrouded in mystery just as that of the first. Travis is departing into the vastness of America, a country where indeed it is possible to lose oneself and to remain missing for as long as one might wish. It’s no small coincidence that director Wenders has a professed interest in road movies such as Easy Rider and has made his own, most notably 1974’s Alice in the Cities and 1976’s Kings of the Road. Speaking about how he tends to begin with road maps, rather than scripts, the German director acknowledged how Paris, Texas had more of a structure, more of a definite narrative to it than his earlier films. Initially, he had wanted to take the film all over America (just as he’d done with Kings of the Road in Germany), but Sam Shepard convinced him to focus instead on the state of Texas as this was America in microcosm. Wenders drove the length of the US-Mexican border as part of his research and came to agree with the writer with respect to the Lone Star State. Of no little interest also is the fact that the director has written about the towns and cities of varying sizes which feature in this film. He has stated for the record that Houston is one of his favourite American cities and that the Los Angeles he presents here is intended as a large suburb rather than a city.

The near-boundless nature of the modern-day city and its infrastructure is examined visually through the photography of Wenders regular Robby Muller and in several telling scenes. One particular highlight for me is a sequence which has no narrative significance whatsoever involving Travis walking along an overpass as a deranged man screams at the passing traffic like a voice in the wilderness. ‘There will be no safety zone!’ he screams to no discernible effect. ‘I can guarantee you the safety zone will be eliminated!’ There is a focus on the paraphernalia of the contemporary world in Wenders’ vision of America which one cannot help but notice. Walt works in billboard advertising and one scene has him preparing a large image of singer-actress Barbra Streisand; upon his return to the civilised world, Travis is fascinated by traffic and the planes he watches taking off and landing at L.A. Airport; later, Hunter and he track Jane down to a drive-through bank in Houston; father and son communicate with walkie talkies as they journey from L.A. to Texas; Hunter wears a NASA jacket for much of the road trip; and then, of course, there is the aforementioned use of telephones and one-way mirrors at the peep show club. The theme of communication, and past failures to do just that, is more than hinted in the way Travis elects to sit with his back turned to Jane in the booth even though she cannot see him. When she realises that it is him, Jane also adopts this body position whilst telling her own story. In a similar vein, Travis is unable to tell Hunter face-to-face that he must leave and chooses a tape recording as a substitute device. ‘I came back to show you I was your father,’ he says in this recording. ‘You showed me that I was.’

This is the quest for redemption which Travis has attempted, but has it fallen somewhat short in the end as he decides not to re-join his family we ask ourselves. In the documentary The Road to Paris, Texas, Wenders talks about the difficulty he always experiences in coming up with endings to his stories. Actor Harry Dean Stanton also comments here on the mixed feelings he still has about that very ending. But would a happy one seem appropriate to us the viewer? Paris, Texas in a sense forces us to confront the very device of constructing a narrative. There is no ideal ending which presents itself if one considers the madness and ill-temperate ways which Travis acknowledges in the final third of the film. The film reaches its conclusion with the beginning of yet another journey. The road is undetermined and endless. Again, I emphasise here the point that this is a country where individuals such as Travis and Jane have become lost because it is partly in their nature and also a manifestation of the environs they find themselves in. The place Paris, Texas may well exist, but on a metaphorical level it is indeterminate and undefined. One senses that Travis will never quite get there. He may well have been conceived in the place, as he believes, but he never will truly belong to it.

Paris, Texas is one of those haunting films that rewards repeated viewings with respect to its stellar performances, distinctive visuals and the wonderful direction of Wenders. Shepard and Carson’s script – though somewhat cobbled together as filming progressed – is as elegiac as that of the memorable score by musician-songwriter Ry Cooder. With respect to the slide-guitar music, Wenders spoke of how its recording was like shooting the film all over again; it’s a near-perfect example of music tailored to images. The Palme d’Or winning film – which also won a Best Director BAFTA award for Wenders – is one to be treasured with respect to the many elements and themes which make it the director’s masterpiece. Worth catching once, twice, an endless number of times. And watch, in particular, for that climactic scene between Dean Stanton and Kinski. ‘I knew these people…’ Wonderful acting and superior film-making.