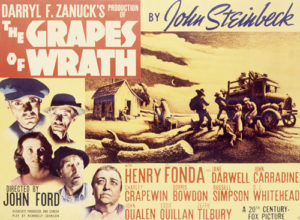

Movie Retrospective: The Grapes of Wrath

Correctly described as a work of realism, John Steinbeck’s 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath was quickly snapped up by Hollywood and released to much acclaim in 1940. Set during the Great Depression of the 1930s, Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize winning work focuses on the Joads, an underprivileged family of tenant farmers who hail from the south-central state of Oklahoma. The historical context which relates to the term ‘Okie’ is significant here and will serve to inform any first-time viewing of this superb film directed by the legendary John Ford and produced by Darryl F. Zanuck. In 1930s America, the word and its usage took on a distinctly derogatory tone. ‘Okie’ was used to describe migrant workers from the state of Oklahoma who traveled largely to California in the hopes of much-needed work and better prospects. The journey westward was arduous and many a dream came to grief in transit or at the point of destination in the so-called promised land. It’s interesting in this respect to note how John Ford – the director most associated with the Western genre in film – was chosen for this project and captured the tenor of Steinbeck’s novel so effectively. A conservative with respect to his political leanings, Ford was an atypical choice for the adaptation, but the direction and aesthetic style which he imposes on the film is unmistakable and deeply-felt to this very day. The completed work earned him one of the four Oscars he won for Best Director during his lifetime.

The film version of The Grapes of Wrath opens quite starkly with the image of a solitary man walking on a deserted road. Plainly dressed, he comes to a store named Cross Roads (quite appropriately) where he hitches a ride from a reluctant truck driver. The familiar face of Henry Fonda leaves us the viewer in little doubt as to the central character of the piece. The man’s name is Tom Joad; he has recently been released from the penitentiary having served four years for the crime of ‘homicide.’ Joad explains to the driver that his father is a sharecropper. We get a sense that he may be out of touch with the social and economic situation on account of the time he has served behind bars. This proves to be the case indeed when Joad encounters the character of Jim Casy (John Carradine) close to his parents’ home. A despondent Casy informs Tom that he is no longer a preacher – ‘Lost the spirit…maybe there ain’t no sin and there ain’t no virtue. It’s just what people does.’ Surprised perhaps at the forthright nature of this revelation, Tom expands somewhat on the details of his previous misdemeanour – he killed a man in a dance hall and hasn’t seen any of his family members since then. Tom and Casy approach the former domicile of the Joad family with an appreciable sense of foreboding. The first-time viewer will be struck by the many night-time scenes which seem to dominate Ford’s film. The director of photography Gregg Toland was famed for his innovative approach (most especially with regard to deep focus) and would cement his reputation just a year later with his work on Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane.

Tom and Casy are informed by a man named Muley Graves (John Qualen) that the Joad family have been forced from the land and are intending to make the long journey to sunny California. Graves is unreserved with regard to whom he blames for his own plight and that of many others including the Joads. In a pointed flashback, we see Graves being handed the written order to abandon his own sharecrop by the deed holders – ‘They came and pushed me off…there ain’t nobody ever coming back.’ A note of cautious optimism is struck the following day when Tom finally catches up with his family. Reunited with his parents, the bond with his mother (Jane Darwell) is especially of note and develops into perhaps the most affecting relationship in the story and film. The relatively happy scene is disrupted as a superintendent appears and reminds Tom’s Uncle John (Frank Darien) that he too must quit his property on the following day. The family of twelve, with Casy in tow, prepare to leave the environs of the Dust Bowl for good, but have to prevail upon the character of Grandpa Joad to accompany them. The elderly man – who had previously spoken of the oranges and grapes in California – has a sudden change of heart which is in keeping with the themes of uprooting and displacement – ‘I ain’t going to California. This is my country and I belong here.’ A cup of coffee laced with soothing syrup renders the aged man docile, but he becomes the first casualty of the journey as he soon passes away on the road.

The first inclination that all may not be quite rosy in the promised land of California comes when the family spends the night in a camp surrounded by fellow travelers. The notion that the western state will provide sustenance and alleviate hardship is scoffed at by an embittered man who has lost his wife and two children due to poverty. The handbill which Tom’s father clutches is viewed as little more than a piece of false publicity; its promise of a robust future is a falsehood designed to lure these people in and exploit them to the nth degree. Fearing that his film might be perceived as pro-Communist, Darryl F. Zanuck hired private investigators to help him legitimise the film and its attendant themes. Upon being informed that the plight of the Okies was indeed severe, the All About Eve producer felt that he could duly defend the film. He was also helped by the fact that the on-going world war (which America would become involved in following Pearl Harbor) amounted to a brief respite for Communism from American demonising. The rickety 1926 Hudson Super Six sedan bearing the Joad family passes through the state of Arizona where we see signs for the Will Rogers Highway and the Colorado River. As they lay eyes on the state of California for the very first time, the mood of the clan is still generally upbeat and infused with hope. Tom’s father refers to it as the ‘land of milk and honey.’ The biblical allusion here is quite clear – having been exiled from their own country, the displaced people now hope for the riches of the promised land where abundance will supplant destitution. In a visual context, Ford and Toland represent this with a vista of orange trees and haystacks. The passing of Grandma Joad at this particular juncture is presented as somehow fitting in this regard. ‘She got to lay her head down in California after all’ Tom’s mother remarks in a decidedly philosophical way.

The family’s change of location does not amount to a change in their collective fortune however and we are reminded of this as they pass another night in a transient camp. ‘None of them look too prosperous’ Tom says; such a remark is further underlined as Ma Joad allows some poverty-stricken children to have the remains of the family’s dinner. Trouble soon ensues as a dodgy land employer shows up at the camp with the sheriff and has an argument with a man who has been conned into labour without pay in the recent past. Attempting to intervene, Tom is reminded that he is still on parole and should lay low. Casy takes sole responsibility for having knocked out the lawman and is taken away by the authorities. Upon learning that some men in the local town plan to burn down the camp, Tom prevails on his other family members to quit the place immediately. As they depart, the family is confronted on the road by an angry mob who tell them they want no more ‘Okies’ in the town or the vicinity for that matter. Again, a false dawn comes to pass in the narrative as the family learns of a ranch (named the Keene Ranch) where they will be hired for picking peaches. The large presence of police outside the ranch does not bode well and the Joads are informed that they will earn a paltry five cents a box. Circumstances inside this settlement are even more inequitable given that the local store charges exorbitant prices for its food and products. An increasingly exasperated Tom meets Casy who is now staying in a tent on the ranch. Casy informs Tom of an impending strike which is due to take place arising from the unfair working conditions therein. The secret meeting of the so-called agitators is broken up as the camp guards descend upon them. At the very end of his tether, Tom kills one of them after Casy has been mortally wounded by the same man. The following morning Tom learns from his mother that the authorities are looking for him – ‘We’re cracking up Tom. We ain’t no family now’ she tells him as she bemoans the gradual demise of their once closely-knit family unit. The Joads decide to leave the ranch when they learn that two-and-a-half cents is as much as they will be paid now per box. They arrive at another camp which is run by the Department of Agriculture. The conditions here are much better than in previous settlements and the family soon adapt to the idea of indoor toilets and showers, facilities which the younger members of the clan had never seen before.

The men, including Tom, are warned of some impending trouble involving the ‘reds’ and so it comes to pass at a dance the following Saturday night when some men attempt to provoke a riot in the camp so that the powers-that-be will be forced to intervene. The savvy Okies manage to avoid such trouble, but their adversaries persist in their efforts to create it. Fearing that he will be eventually found and arrested, Tom decides to leave. Telling his mother that he is determined to find a solution to their overall problem, he says goodbye in one of cinemas most memorable farewells – ‘I’ll be all around in the dark. I’ll be everywhere. Wherever you can look. Wherever there’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beating up a guy, I’ll be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad. I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry and they know supper’s ready. And when the people are eating the stuff they raise, living in the houses they built, I’ll be there too.’ Following Tom’s departure, the family move on once more in the hopes of better things to come. The more upbeat ending to the film contrasts to the original novel which was distinctly bleak in its denouement. Given that Steinbeck’s book concluded with Rosasharn delivering a stillborn baby and, later, offering her milk-filled breasts to a starving man, it’s little wonder that the filmmakers decided to omit such a pessimistic and graphic ending. Bear in mind that these were still the days of the Hays Code in Hollywood. Powerful and influential as they were in the industry, neither Ford nor Zanuck would have managed to get this particular image up on the big screen. The screen adaptation of The Grapes of Wrath ends with Ma Joad declaring quite emphatically that she won’t ever ‘be scared no more.’ The remainder of her speech is in keeping with the defiance and determination expressed by Tom previously – ‘We keep a-coming. We’re the people that live. They can’t wipe us out. They can’t lick us. We’ll go on forever Pa because we’re the people.’ The final image that Ford leaves us with is that of a sun-drenched road in California as a caravan of Okie automobiles continue in their quest for an improved existence and a sustainable future.

Released in January 1940, The Grapes of Wrath opened to universal acclaim and its sizable reputation remains fully intact to this very day. Ford’s film is a telling social document – in the same vein as the novel on which it is based – and there are themes and vignettes which have a relevance no matter what generation or epoch. Watching it again, I was struck by elements such as the artistic endeavour of Ford and Toland in crafting images of a landscape and countryside which are in part benign, but also quite unforgiving. The night-time sequences (and there are quite a few of these as I have noted) seem an extension of the director’s notable interest in German Expressionism. Gregg Toland – who died at the far-too-young age of 44 in 1948 – was the perfect complement to John Ford in this respect. Even the day-time scenes are infused with a sort of desolate poetry. The Dust Bowl which the Okies leave has proven to be unremitting in its particular cruelty; the sun-beaten vistas of California similarly have an arid quality to them. A great film truly becomes a classic based on its leading performances and, in this respect, the two stand-outs in the cast are Henry Fonda as Tom and Jane Darwell as Ma Joad. Fonda was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role (he lost out to James Stewart in The Philadelphia Story) and Darwell won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. The film’s only other Academy Award was bestowed on John Ford (who won again the following year for 1941’s How Green Was My Valley). The Grapes of Wrath was one of ten films nominated for Best Picture at the 13th Academy Awards and, although it did not win (the winner that year was Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca), its place and standing in classic Hollywood has long since been secured. An utterly absorbing melodrama which is poignant, powerful and socially engaging with respect to its headline themes.