Movie Retrospective: The Hired Hand

After the huge success of 1969’s Easy Rider, producer, star and co-writer Peter Fonda did a very strange thing. He directed an elegiac western called The Hired Hand which was released by Universal Studios in August 1971. Described by director Martin Scorsese as a ‘moody, expressionistic and autumnal’ piece, the film is a story about life choices, responsibility, forgiveness and efforts to atone for the past. The setting is the American Southwest during the days of frontier life. In a dreamlike opening sequence (over the film’s opening credits), we watch as one man bathes in a river in front of another man. There are shimmering colours and a general quality of other-worldliness. The character in the water (Fonda’s?) jumps up and down, beating the water in apparent euphoria. Is he celebrating something we ask ourselves or merely taking pleasure in the moment.

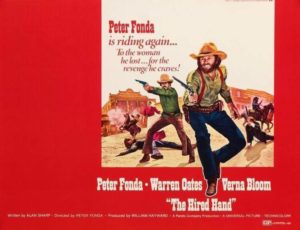

Harry Collings (Fonda) has spent the last seven years of his life wandering around with his best friend Arch Harris (Warren Oates). But Harry has grown tired of their nomadic existence in spite of the freedom and lack of obligation he has enjoyed. Arriving in a tumbledown place called Del Norte, he announces his decision to return to the wife he deserted all those years ago to Arch and their younger companion Dan Griffen (Robert Pratt). Thoughts of heading out to the coast (California) no longer hold an appeal for him in this changed mindset of his – ‘Home is just a place you start from Arch. Maybe there’s something there.’ Suspecting that they have been in this particular town before, the two men are suitably provoked when the rather innocent Dan is killed by a character named McVey (Severn Darden) who claims that the younger man had been molesting his wife. It’s a lie of course and the two men exact revenge the next day by wounding McVey and one of his henchmen. Upon its initial theatrical release, The Hired Hand was marketed as a revenge piece by a studio which wanted to make a quick buck based on Fonda’s name and the aforementioned success of Easy Rider. ‘Peter Fonda is riding again…to the woman he lost…for the revenge he craves!’ read the original cinema poster in such a vein. But The Hired Hand is most definitely not a blood-soaked exercise concerning the theme of vengeance. Fonda and his scriptwriter Alan Sharp had a much more subtle narrative in mind. One which they hoped would strike a chord with revisionist opinions of the day.

Harry’s wife Hannah (Verna Bloom) is less than enamoured by his sudden return after such a lengthy period away. How could she feel any other way? What motivation has brought her husband back now she must surely ask herself. Forgiveness? Loneliness? Or a basic world-weariness which he seems to carry in his very posture? As an interesting aside, we have learnt that Hannah is ten years older than Harry and that they’d lived together as husband and wife for one year and nine months. ‘She had a nice voice’ Harry recalls to Arch on the road home. The latter has put off his plans to travel to California for the moment at least. Perhaps he is curious to see how a possible reconciliation between Harry and Hannah might play out. Perhaps – like Harry – he is simply desiring a comfortable bed once more. But neither of them get this as the strong-willed Hannah orders them to sleep in the barn and work for their basic keep. Suggesting that he serve as her hired hand, Harry also agrees to Hannah’s request that he not identify himself to their daughter Janey (Megan Denver). Janey is under the impression that her father is long since dead. Perhaps she believes that he died heroically or in some other such circumstance. Sharp’s lean script never elaborates on this point.

Frustrations soon rise to the surface as Hannah expresses her opinion (to Arch) that Harry will desert her again before long. The life that he says he has grown tired of still holds its certain charms she supposes. And she also senses the strong bond which exists between Harry and Arch. The two men have had each others back for a long time now and this is a durable relationship, an entity which is deep-rooted. If Arch leaves, as he must do at some point, then what of Harry’s conviction to remain? Will his resolve weaken? Will he yearn for life on the road once more? When Harry learns that Hannah has been no paragon of virtue herself in the intervening years, he confronts her on this matter, and receives a riposte which is unsurprising and entirely justified given the circumstances he himself has created. ‘I walked about this room at nights like this going crazy for a man, any man, didn’t matter’ she tells him laying out the details in a plain and concise manner. ‘And sometimes when there was a man out there, he knew about it, and he’d come in. Sometimes I’d have him or he’d have me, whatever suits you. But not all of them. And not every time I wanted to. And when the season’s work was over, I’d pay him, no matter how well he worked or how well he pleased me. ‘Cos a man in a woman’s bedroom thinks he’s her boss. And sooner or later they’d start to move their tackle out of the shed and in here and I didn’t want that. ‘Cos I already had one man in here and I didn’t want another.’ In another pivotal scene (also involving the excellent Bloom), Hannah confides to Arch the feeling of abandonment she felt in the interim since Harry’s abrupt departure. Can she ever trust him again is the overriding question on her mind. Can he be depended upon? ‘You want him ma’am, you’re going to have to tell him. And you’re going to have to tell yourself too’ Arch advises her in a sagely manner. The scene in question is also notable on account of the fact that he strokes her feet tenderly as he imparts this recommendation. Are Fonda and Sharp suggesting an attraction between the two in spite of Harry? Certainly, Hannah appears to have a better grasp of what caused her younger husband to leave home in the first place. ‘He’s what you went looking for’ she observes to Harry after Arch has declared his intent to move on and seek a new life in California. But Hannah wants an assurance that Harry is choosing to stay with her and Janey because he genuinely wants to, not because he is simply tired of wandering about. In this latter respect, she shows herself to be a powerful self-sufficient woman who is unwilling to compromise or settle for a half-hearted arrangement. Her message to her husband pulls no punches – this time around you have to stay for the right reasons. If you can’t find them now, then you should just leave again.

After Arch departs (‘I’ll bring you back a bottle of that ocean water’), Harry returns to his wife’s bed and a blissful resolution presents itself for a brief moment. But the appearance of a lone horseman sent by McVey quickly puts paid to this idyllic set-up. It transpires that McVey’s men have intercepted Arch on the road and are holding him against his will. For every week that passes, they will remove one of his fingers and then other various body parts. The gauntlet thrown down is that Harry must travel to Del Norte and try to rescue his best friend. Hannah attempts to talk him out of this naturally, but Fonda’s character is unwavering in his determination. In this regard, The Hired Hand adopts the conventions of a classic western in light of how the central character decides to act in a moment of stark crisis – a man’s got to do what a man’s got to do and so on. In this particular scenario Harry doesn’t feel he has a choice, nor is there a suggestion of hesitancy on his part. His friend – who he rode with for seven years – is in dire trouble; of course he must go to his assistance. He promises Hannah he will return, but a sense of foreboding prevails. This is confirmed in the film’s climactic scene as Harry is gunned down by McVey’s men. Dying in Arch’s arms, he implores his friend to hold him. Does this imply a fear of death or an acceptance of the life choice he has made on this occasion? A question which came to my mind as I watching the film again was – what if it were Hannah crouching over him instead of Arch? Would he ask her to do the same? Or would he beg for her forgiveness as he is now leaving for all time? In the final few frames of the film a despondent Hannah watches on as Arch returns by himself to the farm. It’s unclear if he has brought back Harry’s body, but she fully understands what has happened. There are no words exchanged between them. Arch simply goes into the barn and the end credits roll.

A financial failure on its initial theatrical release, The Hired Hand received a restoration and much-overdue re-release in 2001 and was the subject of renewed critical interest. The consensus generally was that this was one of the finest westerns of the 1970s, deserving its place with the likes of Sam Peckinpah’s The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970) and the same director’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), as well as Clint Eastwood’s The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976). No matter what your opinion of it, the film remains a most curious piece and its unhurried narrative reflects the intentions of its director and writer to capture a moment in time when individual lives are practically in a condition of stasis as the world continues to move forward around them. The three central characters – Harry, Hannah and Arch – all have important life choices to make, but first there is this period of deliberation which must take place. For some viewers, the pacing of the film may seem uneven, but this is a conscious decision on Fonda’s part I think. Other fine choices he made in his first film behind the camera were those of Vilmos Zsigmond as his director of photography and folk musician Bruce Langhorne for the score. Fonda passed away in August 2019 at the age of 79. His co-star Verna Bloom died a mere seven months before him at the age of 80. The late great Warren Oates did not get as long as these two – the star of films such as The Wild Bunch and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia died at the much-too-early age of 53 in 1982. A considered meditation on matters such as duty and friendship, responsibility and personal freedom, this unorthodox western certainly merits a repeat viewing and has earned its place in the canon of the genre, as well as 1970s American cinema. To the actors who inhabited their roles so effectively in the film, we raise a glass in praise.