Movie Retrospective: The Philadelphia Story

The romantic comedy film has had countless iterations over the years, but, as with so many film genres, for some of its very best examples we find we must look back at the bygone cinematic era of the 1930s and 1940s for the classic editions in this particular canon. It’s not a gross exaggeration to say that the late great Katharine Hepburn featured in more than a few of these during the course of her prodigious career. 1938’s Holiday and – to a lesser extent perhaps – Bringing Up Baby (more screwball comedy really, although there is an undeniable romantic strain as well) qualify in this regard and then there were her several collaborations with Spencer Tracy in the 1940s and 1950s – Woman of the Year (1942), Adam’s Rib (1949), Pat and Mike (1952) and Desk Set (1957). The much loved and lauded actress retains her star quality on screen to this very day, which makes it all the more difficult to imagine that, by the end of the 1930s, following a series of commercial flops (including the aforementioned Bringing Up Baby), she was considered box office poison. But then Hepburn did something very smart and typically resilient of her. Leaving the bright lights of Hollywood behind, she sought a comeback vehicle by way of Philip Barry’s new play The Philadelphia Story. A certain Howard Hughes purchased the film rights for her before the first curtain rose on opening night. The gamble paid off in the best sense of a Hollywood ending. After 417 performances during its initial run, The Philadelphia Story was a financial and critical hit. Katie was on her way back to Tinseltown and she would never stumble in so overt a manner again.

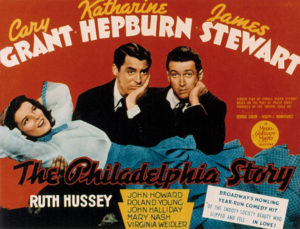

Word has it that Hepburn wanted Clark Gable to play the part of C.K. Dexter Haven and Spencer Tracy to play the part of Macaulay ‘Mike’ Connor. Neither of these came to pass as we know. Having sold the rights to MGM, Hepburn selected George Cukor to direct and agreed to James Stewart and Cary Grant (who received top-billing) as her co-stars. Before principal photography began in July 1940 (they turned films around expeditiously in those days), the actress was heard to remark that ‘I don’t want to make a grand entrance in this picture. Moviegoers think I’m too la-di-da or something. A lot of people want to see me fall flat on my face.’ Cue the film’s very first scene therefore in which Tracy Lord (Hepburn) and C.K. Dexter Haven (Grant) part ways in hardly the most amiable of terms. Having broken one of her soon-to-be ex-husband’s golf clubs, Tracy is pushed to the ground by Haven who – for the very briefest of moments it seems – considers socking her in the face. Mild suggestions of domestic abuse aside, the tactic was to elicit audience sympathy for Hepburn’s character. It worked. They laughed and then began to love her once again.

The Philadelphia Story has been correctly described as a comedy of manners with respect to its musings on the class system (Patrician in this particular case) and some of the misconceptions and concomitant prejudices which surround it. It’s not a screwball comedy as some have suggested, but fits more appropriately in the category of a comedy of remarriage which was then popular in the 1930s and 1940s (other famous examples include The Awful Truth (1937) and His Girl Friday (1940) – both of which starred Grant). The plot is simple really, but fashioned with a suitably devious streak – two years after her divorce from Dexter, Tracy is set to marry the handsome but entirely vapid nouveau riche George Kittredge (John Howard). The self-made man may well be the ‘man of the people’, but he can barely mount a horse or tell which part of the boat is the stern and which is the bow. Meantime – as a backdrop to all of this – Dexter has hatched a cunning scheme which will allow him access to the matrimonial mansion where Tracy and her family (mother and sister played respectively by Mary Nash and Virginia Weidler) reside. Spy magazine publisher Sidney Kidd (Henry Daniell) is eager to cover the social wedding of the year and is only too happy to assign the task to a disgruntled journalist by the name of Macaulay ‘Mike’ Connor (Stewart) and photographer Liz Imbrie (Ruth Hussey). Although Connor is resistant to this type of sordid work as a matter of principle, he is reminded by the practical Imbrie that he must eat. Short stories do not put food on the table just as ethics do not pave the way for personal progress in this world.

Tracy is less than impressed with this ruse, but has little option except to go along with it when she is reminded by Dexter of her father’s infidelity (which Sidney Kidd has been threatening to expose in his gossipy magazine). It’s the first notable moment in the film whereby Tracy’s rather dogmatic streak is referred to explicitly and Dexter takes the opportunity to remind her of their own marriage in this respect – ‘You’ll never be a first class human being or a first class woman until you’ve learned to have some regard for human frailty.’ Not too long after this, her returning father, Seth Lord (John Halliday) remarks in a similar vein – ‘You have everything it takes to make a lovely woman except the one essential: an understanding heart. And without that you might just as well be made of bronze.’ The Philadelphia Story presents us with a strong-willed individual woman, who is not afraid to give as good as she gets, and it depicts her transition to the status of a ‘first class woman’ (as Dexter puts it) without reducing or devaluing her character in any way. In this latter regard, the film is a progressive piece and certainly enlightened with regard to its subject matter. The lesson which Tracy learns through the course of the film is not just how to be a better human being, but also to acknowledge that her previous exacting standards of family and friends have been unreasonable. An attraction which forms between herself and the journalist Connor (who is also biased, but in a different way) allows Tracy to literally let her hair down. It’s also the occasion for one of the best sequences in the film, namely the night before the wedding wherein the normally abstemious Tracy gets inebriated and goes for a midnight swim with the similarly-intoxicated Mike.

The upshot of all this, of course, is that Kittredge suspects the worst of Tracy who – in turn – takes exception to his lack of faith. With a roomful of wedding guests awaiting her ceremonial march down the aisle, Tracy panics and attempts to come up with a plausible excuse for a postponement. Ever the noble figure of the piece (as he imagines himself), Connor steps in first and offers to marry her since he’d got her ‘into this situation in the first place.’ But Tracy and the audience know that Mike is not the right man for her and the plot is perfectly resolved as Haven proposes their remarriage. Preparing herself for a most beautiful wedding, as she calls it, Tracy also makes amends with her father who is standing by to give her away. In a parting shot (a freeze frame of the main characters – Hepburn, Grant, Stewart and Hussey), the persistent and previously-unseen Kidd clicks a picture of the event for the benefit of his Spy magazine readers. It’s one of those essential images of classic Hollywood which speaks volumes of that era’s ambience and sheer quality, as well as framing the wonderful actors who have essayed such memorable characters.

A repeat viewing of this classic comedy some 80 years after its release confirms to this writer (at least) the salient fact that The Philadelphia Story is a film about the embracing of a spirit of tolerance in the personal space and in the public sphere. We witness this in the three main characters of the narrative, most especially Tracy and Mike. The latter, as I’ve previously suggested, presents himself as a man of principle who – at the beginning of the film – is adamant that he will not sacrifice his lofty values for the sake of conformity or convention. But this is precisely what he does of course when he accepts the assignment from Sidney Kidd. Connor’s views on class are also proven to be more than blinkered as the plot of the film progresses. His personal admiration for Dexter grows in tandem with his distaste for the so-called ‘man of the people’ George Kittredge. So too – more plainly obvious and clearly articulated – is his physical attraction for Tracy (who has previously called him ‘an intellectual snob’). When he finds her in the public library reading his collection of short stories (which has not exactly been a bestseller we are informed), his change of attitude towards Tracy is quite remarkable, culminating with the wedding proposal at the end of the film. If Tracy had accepted him as her husband on the spur of the moment, then what kind of man would Mike have become we ask ourselves. Would he have abandoned his ideals entirely and adapted to the manner and ways of mainline society? Or would he have resisted it quietly, with a perpetual grimace on his face? Personally, I don’t think such a resolution would have satisfied anyone – audiences back then or contemporary ones of the present age.

Tracy’s evolution during the course of the film is also notable and deserves some consideration. The scene in which she labels Connor ‘an intellectual snob’ is important in this respect because it concludes with her declaration to him that ‘The time to make up your mind about people is never.’ Now let’s examine that rather sweeping statement in the context of what we already know to this point. Tracy’s first marriage to Dexter has failed for a number of reasons, but one of these is her lack of tolerance as regards his drinking and his carefree attitude. In point of fact, she did make up her mind about him and she has also done so with respect to her father and his philandering inclinations. Her holier-than-thou attitude is her least attractive feature, as identified by both her father and her ex-husband – ‘She finds human perfection unforgiveable.’ Elsewhere, in the film, this side of her is described by Dexter as ‘Your prejudice against weakness…your blank intolerance.’ But – in her very own words – Tracy does not want to be worshiped ultimately, she wants to be loved and this innate desire within informs much of her development throughout the film. When she forgives her father and accepts Dexter at the end, we sense that her personal growth is complete. No longer engaging in priggish behaviour, she has become forbearing and will surely be a more understanding partner to Dexter the second time around. The remarriage in this film also represents the spiritual awakening of Tracy Samantha Lord.

Nominated for a total of six Oscars at the 13th Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actress (Hepburn) and Best Director (Cukor), The Philadelphia Story won two for Best Actor (Stewart) and Best Adapted Screenplay (Donald Ogden Stewart). It rose to 44th place in the American Film Institute’s 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) List in 2007 and retains its classic status to this day thanks to the memorable performances of the central cast, the adept direction of Cukor and the wonderful adaptation of Philip Barry’s play by Ogden Stewart. It’s yet another reminder of the high-quality entertainment which old Hollywood aspired to and so often succeeded in pulling off with consummate skill. Lest we ever forget vintage productions of this nature, or actors of the calibre of Hepburn, Grant and Stewart. An affair of manners and of personal improvement to remember.