Music and Movies: 10 Examples of Great Film Scores

There is a theory that film music did not start out for any particular aesthetic purpose, but rather for a most practical one, namely, to drown out the noise created by projectors in those early days of the silent era. This may well be the case and one can imagine sitting in an auditorium in that bygone age with only the sound of a humming apparatus in the background. This would never do for a comedy of Chaplin’s or a romantic piece involving Rudolph Valentino. Rex Ingram’s The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse would surely be far less effective if it were bereft of the score by Louis F. Gottschalk. The same could be said of Wallace Worsley’s 1923 The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Chaplin’s 1925 The Gold Rush and King Vidor’s The Big Parade from that same year. Can one imagine watching that final heartbreaking scene from The Little Tramp’s 1931 masterpiece City Lights (by which time of course the talkies were established) without the accompanying score by the great man himself. And what indeed of his subsequent Modern Times and The Great Dictator with their own distinctive compositions? Film music has been with us now for nearly as long as the art form itself. We fully expect to hear an original piece by Hans Zimmer, Alexandre Desplat or Michael Giacchino, or a veteran in the mould of John Williams or Ennio Morricone, as the lights fade and the opening credits begin to roll. Music in films is as intrinsic and integral a component as the performance of an actor or the cinematography of a DOP. Good film music amplifies the effect of proceedings on the screen. Great film music has an uncanny way of entering the popular culture and becoming an artistic entity in itself.

Let us consider what some of the films I’ve listed below would be like if all we had was dialogue and visuals. The aforementioned City Lights is a truly wonderful tale on its own merits, but what if Charlie had chosen to present it without that sumptuous score. How exactly would that scene in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, as Jimmy Stewart sees Kim Novak for the first time, play without the haunting music of Bernard Herrmann? And what of the director’s subsequent Psycho and those screeching string instruments as Janet Leigh is attacked in the famous shower scene? Herrmann’s highly original piece – simply titled The Murder – intensifies the feeling of horror as those knife thrusts connect with the ill-fated heroine. Elsewhere, is it possible to overlook the contributions of composers such as Maurice Jarre and Elmer Bernstein to the epic adventures that are Lawrence of Arabia and The Great Escape? Italian composer Ennio Morricone formed a memorable collaboration with fellow countryman Sergio Leone in that director’s Dollars Trilogy, Once Upon a Time in the West and the later Once Upon a Time in America. Nino Rota – who hailed from Milan – also enjoyed a lengthy and productive alliance with Federico Fellini. His most famous score, however, is that of the music he wrote for the 1972 crime epic The Godfather and its subsequent sequel. Would the intricate machinations of Marlon Brando or Al Pacino seem more or less justifiable in the absence of that indelible music? I would suggest here that the music reinforces the themes of family and loyalty which Coppola is examining onscreen. And what of John Williams’s famous score for Jaws and its undoubted place in cinema history? As the shark turns to attack the boat once again, can anyone really contend the scene would play just as effectively without that very familiar, yet simple, two-note arrangement? I think not. The same could be said of the composer’s Oscar-winning effort for 1977’s Star Wars. Just think of Darth Vader without the ominous music which accompanies him. There are countless other such examples from the annals of film history – consider John Williams’s work on Spielberg’s 1977 Close Encounters of the Third Kind as the UFOs descend on Wyoming’s Devil’s Tower; or the sheer magic of cinema-going in post-war Italy as relayed in Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso, and perfectly complemented by Ennio Morricone’s beautiful score; the impending sense of peril communicated in Bernard Herrmann’s work in 1962’s Cape Fear and its 1991 remake; or the indelible image of a taxi cab emerging from a veritable fog of haze and steam to the bars of that same composer’s music in 1976’s Taxi Driver. Would Lean’s 1965 Russian epic Doctor Zhivago be quite the same without the memorable Lara’s theme? Or 1984’s Paris, Texas bereft of the elegiac slide-guitar score by Ry Cooder? I could go on and on in this regard, as there are so many cases-in-point, but below see my thoughts on ten films with unforgettable original music and how the scores enhance other elements of each such as the narrative, the visuals and the performances. Enjoy these great films and their wonderful accompaniments if and when you have a chance. Lights down now and cue the music.

City Lights (Charlie Chaplin)

As a child Chaplin had taught himself to play the piano, violin and cello, and as a filmmaker subsequently he more than valued the importance of the musical compositions which accompanied his work. It’s entirely fitting, therefore, that his 1931 City Lights was also the occasion of his first film score, but credit for this should also be apportioned to the likes of Arthur Johnston and Alfred Newman. The screen icon was not a trained musician himself (he couldn’t actually read sheet music), so he sought the professional help of the Pennies From Heaven composer and the nine-time Oscar winner. Johnston committed Charlie’s improvisations to paper over the course of a six-week time period and Newman recorded it in a matter of five days. The result is something very special indeed in this quite extraordinary motion picture. We are in a very familiar Charlie-like situation at the beginning of City Lights as the Little Tramp is discovered sleeping on a newly-dedicated statue much to the chagrin of the authorities and crowd and this is perfectly reflected in Overture/Unveiling The Monument. Comical flourishes also abound in compositions such as The Millionaire’s Home, The Nightclub, Homeward Bound and, of course, the famous boxing match sequence (The Boxing Match). Consider these in contrast to the music which accompanies the blind flower girl (as played by Virginia Cherrill). The theme here is one of affection becoming love and arrangements such as The Flower Girl and Buying Flowers chart this progression as well as the narrative of the film itself. Regarding that famous final scene, the film critic James Agee wrote that it was ‘the greatest single piece of acting ever committed to celluloid.’ It’s difficult to argue with this statement, but one should also appreciate again how music plays its sizeable part in City Lights as a whole. The main theme for Virginia Cherrill’s character made use of the song La Violetera by Spanish composer Jose Padilla. Chaplin subsequently lost a lawsuit to Padilla for failing to credit him on the film. That point of detail aside, this is Charlie’s score and a wonderful complement to the greatest silent film of them all in my own humble estimation.

Vertigo (Bernard Herrmann)

A good friend of mine once said that Hitchcock invested Vertigo with its indelible style and technique (who can possible forget such tricks from the master as the dolly zoom to create the visual impression of Scottie’s acrophobia), but it was composer Herrmann who gave the film its heart and soul by way of his original score. Personally, I think that’s a wonderful summation and the emotional attachment (and indeed infatuation) which develops for Scottie (James Stewart) apropos Madeleine (Kim Novak) is realised in early pieces such as Madeleine’s First Appearance, The Flower Shop and By The Fireside. But Vertigo is far from being a romantic film remember, and discordant themes in the twisty tale are reflected also in Herrmann’s work – Graveyard and Tombstone, The Bay, The Forest, The Dream and the climactic moment of the first act, The Tower. The famous title sequence – as co-designed by Saul Bass – is composed of spiral motifs intended to evoke in the mind of the viewer the notions of disorientation and obsession. Such is also the case with the music which accompanies this as Herrmann seeks to instil an aural sense of disharmony and malaise within the male psyche. And yet – on a purely personal level – I cannot but emphasise (and eulogise) the romantic overtures which the Oscar-winner harkens back to as Scottie attempts to make Judy over so that she will physically resemble the deceased Madeleine (Goodnight, The Park and the quite incredible Scene D’Amour – as the haunted detective imagines himself back at Mission San Juan Bautista with his beloved). This was one of seven collaborations between Herrmann and Hitchcock (they began with 1955’s The Trouble with Harry and parted ways after 1964’s Marnie) and for me it’s their very best work respectively. Listed as the twelfth greatest film score of all time in the American Film Institute’s 100 Years of Film Scores; should be much higher up that particular list as far as I’m concerned. Watch this classic film again and see (and hear) what I mean.

Psycho (Bernard Herrmann)

You’re immediately thinking of that famous shower scene involving the ill-fated Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), the multiple camera angles and the screeching violins, violas and cellos, aren’t you? Appropriately titled The Murder, this is without doubt the most famous piece from the soundtrack to Hitchcock’s seminal 1960 psychological horror, but let’s not overlook other aspects of Herrmann’s masterly score. Forced to work on a reduced budget for this their sixth collaboration together, the composer wrote for a string orchestra as opposed to a full symphonic one and did not for a moment entertain the director’s initial idea of employing a jazz score. The opening arrangement for the credits sequence – accompanying Saul Bass’s graphic efforts – sets the scene perfectly with its suggestion of imminent menace and overarching jeopardy. The score settles into more seemingly tranquil chords as the rather tenuous relationship between Sam and Marion plays out, but moves up a few dramatic notches again as the heroine absconds with the $40,000 in cash – Flight, The Patrol Car and The Rainstorm. The introduction of Norman (Anthony Perkins) and his subsequent conversation with Marion regarding ‘mother’ is also a particular highlight (‘She just goes a little mad sometimes’) before director and composer jolt us with the aforementioned shower scene. Hitchcock himself had originally intended to employ no music for the sequence, but Herrmann convinced him otherwise. The result is justifiably iconic and reinforces the effect of each of those stabbing motions; just imagine how less impactful it would be without those jarring sounds. The master of suspense was so grateful for this effect, and in an overall context, that he had Herrmann’s name placed in the credits sequence just before his own. He also doubled the latter’s salary as an act of gratitude. It was well deserved. Psycho the film remains to this day a much lauded and imitated film in its genre. Psycho the soundtrack also deserves its rightful place in the category of truly great film scores. Just a shame that Hitchcock and Herrmann never worked together again after 1964’s Marnie.

Lawrence of Arabia (Maurice Jarre)

Another famous partnership between director and composer here as Maurice Jarre and David Lean worked together on four films in total beginning with the 1962 historical epic based on the life of T.E. Lawrence. Jarre, who was little-known at the time, was not the first choice for musical duties in this particular instance and was only given a window of six weeks in which to deliver the orchestral backing to Lean’s panoramic compositions. The Frenchman more than delivered with his monumental score which entirely befitted the grandeur and cinematic sweep intended by his director. With the opening Overture and Main Title the viewer is left in no doubt as to the nature and scale of things to come. The sheer breadth (and attendant perils) of the desert itself is perfectly captured in Nefud Mirage, Sun’s Anvil and That is the Desert. The sense of conflict inherent in the troubled titular character himself is reflected in motifs which inform Lawrence and his Bodyguard, Lawrence and Tafas and Ali Rescues Lawrence. The bittersweet departure of El Aurens from the desert is much in evidence at the film’s end as he sits forlorn in a staff car to the strains of the main theme dropped down quite a few notiches by Jarre. It’s a score of considerable range which won one of the film’s seven Oscars at the 35th Academy Awards. Jarre won two more Oscars for other Lean work – 1965’s Doctor Zhivago and 1984’s A Passage to India – but this remains his personal best. A nicely-timed refrain of the main theme occurs in the 1977 James Bond film The Spy Who Loved Me as Roger Moore and co-star Barbara Bach travel across the Sahara Desert in Egypt. You don’t have to listen that closely for it by the way; it’s surely one of the most recognisable in all of cinema history.

The Great Escape (Elmer Bernstein)

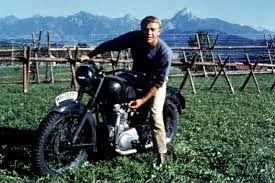

Composer Bernstein had previously worked with John Sturges on the latter’s The Magnificent Seven (which also features stars Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson and James Coburn). The score for that 1960 western, particularly the iconic main theme, has its own place in cinema history, but I’m giving this one the nod ahead of it based on my personal affection for the film itself and the many great motifs which Bernstein introduces as a complement to the characters and their grand scheme. The Main Title introduces that unmistakeable main theme and there are some wonderfully playful pieces which follow including Forked, Cooler and Booze. There are also some poignant strains as well, particularly with regard to Archibald Ives, aka ‘The Mole’ (he’s the one who eventually snaps when the Germans discover the escape tunnel named Tom). Elsewhere, the ever-present physical dangers of the endeavour are represented in compositions such as Cave In, Various Troubles, 20 Feet Short and Foul Up. The section of the film in which the POWs make their way through enemy territory is filled with the tension and peril of detection and possible execution – At The Station, On The Road and Flight Plan. Steve McQueen’s motorcycle heroics are a particular standout for many an Escape fan and that famous scene in which he attempts to jump the barbed wire fence along the German-Swiss border – spine-tingling as it is – would surely not be quite the same without Bernstein’s music. A classic WWII film that is suitably enhanced by its memorable score.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Ennio Morricone)

Morricone had worked on the previous two installments of Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy (he was credited as Dan Savio on A Fistful of Dollars), but his professional stock and reputation rose quite a few levels with this his score for the 1966 concluding entry in the series. A highly original approach was embraced by the Italian composer with respect to his use of diverse sounds such as gunfire, whistling and yodeling in his compositions. Consider that very familiar main title theme with the recurring motif which sounds akin to the howling of a coyote. It’s used, of course, to very fine comic effect in the film’s very final scene as Tuco (Eli Wallach) curses loudly while Blondie (Clint Eastwood) departs over the horizon. Another standout moment in both film and score is that of The Ecstasy of Gold as Tuco frantically searches for the grave of Arch Stanton amidst a virtual ocean of wooden markers. The camera work of cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli is intended to evoke a spinning, near-dizzying effect here which is perfectly complemented by Morricone’s almost overwrought musical piece. The overall symmetry which is achieved is also in evidence in the famous The Trio sequence as Tuco, Blondie and Angel Eyes (Lee Van Cleef) face off in the courtyard of Sad Hill Cemetery. But I would also draw your attention to the moments of poignancy which inform both film and score. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is set during the American Civil War and part of Leone’s thematic design was to portray the futility of such armed conflict. The scene at Batterville prisoner-of-war camp, as Tuco is savagely beaten by Angel Eyes’ henchman to the sorrowful strains of Morricone’s The Story of a Soldier, is one such instance. Later on, we have a very slight variation on this theme with The Death of a Soldier (Blondie comforting a young dying soldier by offering him the remainder of his cigar). It’s an aspect of the film and the music that has perhaps been overlooked in the past, particularly with regard to the attention paid to the main title. But Leone’s vision and range of themes in this 1966 classic is both broad and multifaceted. The same indeed can be said of Morricone’s music.

Once Upon a Time in the West (Ennio Morricone)

Leone made an unusual request here by asking Morricone to compose the music prior to principal photography and one can only imagine how onerous a task this must have been. But the artistic rationale which informed this decision was inherently sound as the director wished to have the music available on the film set and playing during principal photography. It works to devastating effect of course in the above-referenced scene as Charles Bronson’s Harmonica and Henry Fonda’s Frank shoot it out at the film’s climax. And consider also the much earlier Grand Massacre scene as the McBain family is wiped out by Frank and his men. There’s an almost graceful, hypnotic sense of movement to those dusters as they emerge from the undergrowth. And what about the indelible shot of Jill McBain (Claudia Cardinale) as she arrives at the station from New Orleans. Realising that something is not quite right, as there is no one there to meet her, the former prostitute and recently-married woman walks out onto the street as Leone’s camera and Morricone’s music rise dramatically above her. This is the famous Jill’s America theme (with wordless vocals by Italian singer Edda Dell’Orso), one of a number of leitmotifs which Morricone composed for each of the main characters (Jill, Harmonica, Cheyenne and Frank). Once Upon a Time in the West is to my mind a particular high point in the careers of both its director and composer. The two collaborated on eight films together from 1964’s A Fistful of Dollars to 1984’s Once Upon a Time in America. With respect even to the aforementioned The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, it would be difficult to place anything else but Once Upon a Time in the West at the very top of their artistic endeavours.

The Godfather Part I (Nino Rota)

Nino Rota was famous long before The Godfather with respect to his many collaborations with Federico Fellini (17 in total during their respective careers) and his work on other features such as Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers and The Leopard and Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet. In creating compositions for the crime epic, Rota used some parts from the score he’d previously written for the 1958 Italian film Fortunella starring Giulieta Masina and Alberto Sordi. Sadly, this approach backfired to a great extent when, on the eve of the 45th Academy Awards (at which The Godfather won Best Film), Rota’s nomination for Best Original Score was removed owing to this re-use, particularly with regard to the Love Theme. Rota had the last laugh some two years later, however, when he finally won the Oscar for his work on the film’s sequel The Godfather Part II (along with the director’s father Carmine). As for the score itself, one would have to say that the great composer from Milan perfectly captures the themes Coppola explores in his adaptation of Mario Puzo’s best-selling novel which so often emphasise the all-important family unit and the utilisation of coercion and violence in maintaining its pre-eminent position. In this regard, consider such pieces as the aforementioned Love Theme, The Godfather Waltz and Connie’s Wedding. The Machiavellian practices which underpin this world are at the fore in The Pickup, The Halls of Fear and the very famous Baptism montage. With respect to this latter sequence, which juxtaposes the Christening of Connie’s baby with that of Michael’s execution of the other New York dons and Moe Greene, again I would draw your attention to how inferior this device might be were it bereft of music. The same could also be applied to those glorious scenes in Sicily as Michael goes into hiding and meets his first wife Apollonia (Sicilian Pastorale and Apollonia). The song Speak Softly, Love based on the Love Theme was recorded and released by Andy Williams in April 1972. Those opening few bars from the main title itself are unmistakeable and surely evoke that indelible opening image of Marlon Brando’s Don Corleone sitting in his office, cat on lap, as he hears requests on the day of his daughter’s wedding. Unforgettable indeed.

Jaws (John Williams)

Memorable film scores surely don’t come much more memorable than this one. The second of many such collaborations between composer Williams and director Spielberg, one cannot help but feel a tingle down the spine as that famous two-note composition reverberates in the main shark theme. The opening scene of the 1975 film (based on Peter Benchley’s novel of the same name) is effective enough, but just try and imagine the impending attack on the ill-fated Chrissie without that repeated beat as the camera (acting in this instance as the great white’s point of view) rises below her. It’s classic suspense which is sustained both visually and aurally as the story of attacks in and around the fictional town of Amity Island unfolds – Promenade (Tourists on the Menu) – particularly with regard to the Fourth of July scenes. But Jaws the film truly soars when the unlikely triumvirate of Brody, Hooper and Quint head out to sea to hunt the deadly creature. The scenes on the Orca alternate between periods of quiet and some camaraderie (the wonderful USS Indianapolis story as related by Quint) with those of the shark being harpooned with the barrels before turning to attack the boat during broad daylight and under the cover of darkness later on – Sea Attack Number One and One Barrel Chase. The climactic pieces – The Underwater Siege and Hand to Hand Combat – perfectly complement the high drama on screen as Hooper is attacked in the submerged cage and the remaining Brody attempts to shoot the tank (‘Smile, you son of a bitch!). On a purely personal note, I have to say that my own favourite tracks in the film are Night Search, Out to Sea and The Indianapolis Story. Williams has gone on the record to say that he saw similarities between Jaws and good old-fashioned pirate movies and the aforementioned pieces resonate with such motifs. The composer won the Oscar for Best Original Score and it deservedly ranks high up on the list of the American Film Institute. Spielberg himself also recognised the importance of Williams’ endeavours saying that his film would have been only half as successful without it. High praise indeed and thoroughly merited in this particular instance.

The Artist (Ludovic Bource)

Kim Novak probably won’t appreciate the inclusion of this one. The Vertigo star used the word ‘rape’ in connection with the employment of the Scene D’Amour composition from the 1958 Hitchcock film and, overstated as her argument was, there was some merit in it when one considers the otherwise superb work by Ludovic Bource. Much of the French composer’s intent here (as per the Oscar-winning film itself) is to transport us back to that bygone cinematic era of the late 1920s and early 1930s and he succeeds in this regard with wonderful pieces such as At the Kinograph Studios, Waltz for Peppy, On The Stairs, Jungle Bar and Happy Ending. The Artist Overture, which accompanies the opening credits, establishes in our minds the era we are being taken to. Subsequent compositions 1927: A Russian Affair and the absolutely delightful George Valentin (as the central character plays up to the premiere audience) further ingrain this impression. The Artist the film and the music are largely nostalgic in tone, but there are moments of pathos and sadness touched upon as well as George’s career founders with the advent of the talkies (1929, The Sound of Tears and Ghosts from the Past). Happily, of course, an exuberant tone re-establishes itself in the film’s final scene with Peppy and George. There are parallels which one can draw here to Chaplin’s score for City Lights and it’s somehow appropriate that these two ostensibly silent films bookend this list of ten. Quite why someone decided that Bource should not compose the music which accompanies that sequence in which George contemplates suicide and Peppy rushes to save him is beyond me. Kim Novak had something of a point here even with her own personal reasons. The sequence in question probably should have had an original composition to accompany it rather than relying on the work of Bernard Herrmann. The fact that Bource went on to win that year’s Academy Award for Best Original Score further reinforces this very argument. That small quibble aside, a superb original score which more than merits its place on this list.

Okay, that’s 10 great film scores for your consideration, but listed below are 40 more such endeavours which may be familiar to you, or worth checking out if you have the time:

Amarcord – Nino Rota

Ben-Hur – Miklos Rozsa

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – Burt Bacharach

Barry Lyndon – Leonard Rosenman

Close Encounters of the Third Kind – John Williams

Cinema Paradiso – Ennio Morricone

Casablanca – Max Steiner

Chinatown – Jerry Goldsmith

Cape Fear – Bernard Herrmann

Dances with Wolves – John Barry

Doctor Zhivago – Maurice Jarre

Empire of the Sun – John Williams

8-and-a-Half – Nino Rota

E.T. the Extraterrestrial – John Williams

Field of Dreams – James Horner

For a Few Dollars More – Ennio Morricone

The Godfather Part II – Nino Rota

Glory – James Horner

Hiroshima Mon Amour – Georges Delerue and Giovanni Fusco

The Killing Fields – Mike Oldfield

The Lion in Winter – John Barry

The Mission – Ennio Morricone

Mary Poppins – Irwin Kostal, Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman

The Magnificent Seven – Elmer Bernstein

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance – Cyril J. Mockridge and Alfred Newman

North by Northwest – Bernard Herrmann

Out of Africa – John Barry

Once Upon a Time in America – Ennio Morricone

Paris, Texas – Ry Cooder

The Piano – Michael Nyman

The Quiet Man – Victor Young

Schindler’s List – John Williams

The Shawshank Redemption – Thomas Newman

Somewhere in Time – John Barry

Star Wars – John Williams

The Searchers – Max Steiner

Sunset Boulevard – Franz Waxman

Taxi Driver – Bernard Herrmann

The Third Man – Anton Karas

Top Hat – Irving Berlin and Max Steiner

There was a documentary on C4 many years ago about whether Hitchcock’s films would work without Herrmann – and they compared clips from North by Northwest (the arrival at Mason’s house on Long Island) as an example – and unsurprisingly the suspense didn’t work in the same way at all! In fact it played like a comedy! Intriguing choices! I love Le Mepris and Carlito’s Way!