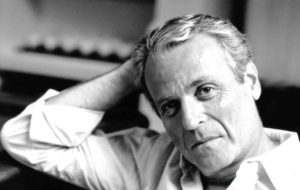

Screenwriter and novelist William Goldman will be sadly missed

If one were to compile a list of the most influential scriptwriters over the past 50 years, then it is reasonable to conclude that William Goldman – who passed away on the 16th November, 2018 at the age of 87 – would probably top the table. The two-time Oscar winner gave us great cinematic entertainments such as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, All the President’s Men, Marathon Man and The Princess Bride during the course of his extensive career. He deserves his place at the top table with the likes of Paddy Chayefsky, Woody Allen, Aaron Sorkin and Waldo Salt, who could also lay claim to a place in this elite company – Chayefsky (Marty, The Hospital and Network) in particular. What sets Goldman apart from these others however are the memoirs he wrote about his experiences of working within the Hollywood system – Adventures in the Screen Trade (1983), Hype and Glory (1990) and Which Lie Did I Tell? (2000). In the first of these books, Goldman coined his famous piece of reasoning apropos the Hollywood cinema industry as a whole – ‘Nobody knows anything,’ he declared, ‘Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work. Every time out it’s a guess and, if you’re lucky, an educated one.’

The kid who was born in Chicago in 1931 had more than a few educated guesses in his time which led to some commercially-successful and critically-lauded films. But like so many other writers, he struggled with his profession at first before lady luck smiled upon him. The son of an alcoholic businessman who took his own life, Bill struggled to have his early works published before his first novel titled The Temple of Gold went into print in 1957. His 1964 novel No Way to Treat a Lady was filmed as a black comedy thriller starring Rod Steiger and Lee Remick. Goldman did not pen the screen adaptation for this one, but clearly the Hollywood bug had struck and he followed it up with 1966’s Harper (starring Paul Newman) which launched his career as a bona fide screenwriter. His first original screenplay, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (which he’d been researching for some eight years), sold for a then record $400,000. The money spent by the studio proved to be an astute investment as the western – starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford – was a box office hit. But, more importantly, it became one of the most beloved films of the era and netted Goldman an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. Who could possibly forget such memorable scenes as the jump from the cliff face or the climactic Bolivian shootout? Goldman gave us those as well as well as a fistful of unforgettable quips between the chief protagonists.

His second Oscar came for 1976’s All the President’s Men based on the 1974 non-fiction book of the same name by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. The complexities of the Watergate scandal, and the difficulties of presenting these in an interesting and lucid fashion, would have been beyond many a scriptwriter, but Goldman handled it with typical aplomb. One of the key contributions he made to the narrative was the decision to end the film with an apparent stalemate in the investigation. The famous catchphrase ‘Follow the money’ was also Goldman’s innovation. All the President’s Men went on to be a commercial hit winning Oscars in four categories including Best Supporting Actor (Jason Robards) and Best Adapted Screenplay (Goldman). The Rotten Tomatoes consensus correctly describes it as ‘A taut, solidly acted paean to the benefits of a free press and the dangers of unchecked power, made all the more effective by its origins in real-life events.’

A number of the novels which he penned in the 1970s were adapted by himself for the screen beginning with 1976’s Marathon Man (based on Goldman’s 1974 novel of the same name). Do I need to say anything about the famous ‘Is it safe?’ scene involving Dustin Hoffman’s Babe and Laurence Olivier’s Szell? I think not. The John Schlesinger directed film was a critical and box office success. 1978’s Magic (based on Goldman’s 1976 novel) was also well-received and is particularly notable for an exceptional turn by Anthony Hopkins as the unstable Corky Withers. Goldman’s The Princess Bride – which was first published in 1973 – did not find its way to the screen until 1987 when it was directed by Rob Reiner. Starring Cary Elwes and Robin Wright, the modestly-successful fantasy has deservedly grown in reputation over subsequent years and is now hailed as one of the very best of its genre. A plethora of memorable cameo appearances include Billy Crystal, Peter Cook and Carol Kane. Irish viewers should also watch out for the Cliffs of Moher which doubles here as the Cliffs of Insanity.

Goldman is known to have made some uncredited contributions to films such as Twins, Indecent Proposal and Last Action Hero in the 1980s and 1990s and he also acted as a consultant on 1992’s A Few Good Men, 1995’s Dolores Claiborne and 1997’s Good Will Hunting; but his bread and butter still remained as a fully-fledged scriptwriter and indelible later works by him include 1990’s Misery (re-teaming with Rob Reiner) and – to a lesser extent – the underrated Charlie Chaplin biopic directed by Richard Attenborough in 1992. Self-critical of his own work, Goldman once said that he didn’t like his writing generally and that Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Princess Bride were the only two things he’d ever written that ‘I can look at without humiliation.’ For a man who has three screenplays on the Writer’s Guild of America hall-of-fame’s 101 Greatest Screenplays list (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, All the President’s Men, The Princess Bride), this was an assertion which was more than a little tough given the volume and quality of his work for several decades. His place in screenwriting history is assured, we are happy to say, in spite of his own articulated reservations. Butch and the Kid will live on in our movie minds for evermore. William Goldman’s sizable reputation will not diminish as long as writers continue to put pen to paper.