The Good, the Bad and the Ugly Celebrates 50 Years

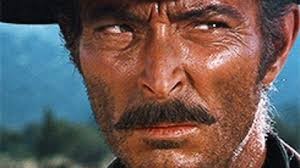

The third and final instalment of Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy is soon to turn 50. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Leone’s epic tale of three gunslingers (as played by Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef and Eli Wallach) seeking a fortune in gold pieces against the backdrop of the American Civil War, was first released in Italy on the 15th of December, 1966. It’s a film which has more than stood the test of time and proven highly influential with both filmmakers and audiences alike. So what is the enduring appeal? Well in the first instance one has to say that it’s a damn good story. You know it very well I’m sure. Aficionados no doubt could relay the plot scene by scene. The Italian director had already broken new ground with the first two parts of his trilogy, but this was the complete deal in terms of storytelling. When compared to A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and For a Few Dollars More (1965), it has to be said that Leone had taken great strides in terms of his skills behind the camera and narrative technique in just a few short years. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is a fitting culmination to the series and also improves upon its predecessors. It took the spaghetti western form into the domain of epic film-making and provided this revisionist sub-genre with several memorable moments and visually-stunning sequences.

War Is Hell: The Civil War which rages in the background is often an impediment to the three main characters in their quest, but it’s also a good starting point in appreciating Leone’s vision and one of the film’s central themes. The director had a keen interest in history and wished to depict the absurdity of war in general. Significant moments in this regard occur at the prisoner-of-war camp at Batterville (as Tuco is interrogated and quite savagely beaten by Corporal Wallace) and, of course, the battle for the strategic bridge which separates the main players from the loot buried in Sad Hill Cemetery. A pivotal line of dialogue in this regard is Blondie’s utterance as he observes the slaughter on both sides – ‘I’ve never seen so many men wasted so badly.’ A short time later we witness him comforting a young dying soldier by offering him the remainder of his cigar. The character of Captain Clinton, whom Tuco and Blondie temporarily befriend, also bemoans the futility of battle as he remarks on the lives he could save if he were able to destroy the bridge. Mortally wounded in a subsequent skirmish, Clinton does get his dying wish when the two blow it sky-high. The 2004 Special Edition includes a deleted scene in which Angel Eyes encounters first-hand the humiliating conditions suffered by Confederate soldiers following an artillery attack. This is a film that doesn’t just de-romanticise the Old West but also takes a very dim view of the nature and toll of warfare generally. Leone makes his points on this very subject with some quite poignant moments. Again it’s a testament as to how far he’d progressed in this particular field. War is neither good nor bad here; it’s just plain ugly.

Revisionist sentiments: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly of course is a post-classical western in the very best sense. There are no heroes here in the John Wayne or Gary Cooper mould. The settings are quite desolate and far removed from John Ford’s beloved Monument Valley. Violence is a commonplace and there is absolutely no honour amongst thieves. Every man – particularly the three principals – is out for himself. Extreme close-ups focus on beady eyes and sweaty countenances. Some of these characters are downright repellent; others, at best, shady and far removed from the heroic figures depicted in Hollywood westerns of the 1930s and 1940s. This was precisely Leone’s intention of course and he’d begun his own deconstruction of the genre with A Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More. There’s no place in this particular west for Wayne’s Ringo Kid or Cooper’s Will Kane. Chances are they, and their intrepid deeds, would not make it to the final frame of this one. What Leone is effectively saying is the romantic west is dead and gone; it may never have existed in the first place.

Tuco is the star: With all due respect to Mr. Eastwood and Mr. Van Cleef, it has to be said that Eli Wallach as Tuco steals the show here. A method-trained actor who studied under Lee Strasberg, Wallach had an innate ability on stage and in front of the camera and his considerable skills are apparent in every scene he appears. If anything, Tuco is the main character of this film; not Blondie perhaps, and certainly not Angel Eyes. Van Cleef himself made such an observation when he remarked that, ‘Tuco is the only one of the trio the audience gets to know all about. We meet his brother and find out where he came from and why he became a bandit.’ The scene Van Cleef is referring to here takes place at the frontier mission where, we learn, Tuco’s brother, Father Pablo Ramirez (Luigi Pistilli), resides. In one of the film’s more telling and superbly-played scenes, the Catholic friar castigates his bandit brother for the immoral life he has led. Tuco responds to this criticism by reminding his brother of the stark choices they faced in light of their destitute background. ‘You chose your way, I chose mine. Mine was the harder,’ he counters. A visibly humbled Pablo silently begs his forgiveness. It’s one of the film’s more poignant moments as the bandit brother departs once more to pursue the life he has chosen. Elsewhere, one has to marvel at such moments as when Blondie falsely delivers Tuco to the proper authorities early on in the film. The string of insults Wallach puts together is expertly-delivered and comically-timed. Or when Tuco executes one of his would-be assassins from the comfort of a bathtub. The final barrage he unleashes at Blondie at the film’s conclusion is complemented by Ennio Morricone’s iconic score. Not bad for a man who was almost poisoned on set owing to a misplaced bottle of acid. Wallach alluded to this occurrence in his autobiography remarking that, whilst he was indeed a brilliant director, Leone had little concern for the safety of his actors. Thankfully, the great actor survived this incident. He lived to the ripe old age of 98 before passing in 2014.

The style’s the thing: I already alluded to those facial close-ups as utilised by Leone, but there’s also a panoramic scope to his vision which was amplified by cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli. This is particularly the case in the desert scenes as Tuco forces Blondie through a slow and harrowing death march, and the later scenes involving the battle for the bridge as mentioned previously. Consider also that hypnotic sequence as Tuco first discovers Sad Hill Cemetery and madly dashes between headstones and grave markers. The camera spins incessantly invoking a near-dizzying effect. Stylistically-speaking the centrepiece is of course the famous Mexican standoff between the principal characters towards the film’s conclusion. There are countless cuts between the three, juxtaposed with long shots of the cemetery courtyard. It’s an iconic sequence and is accompanied by Morricone’s composition aptly titled The Trio. Which brings me to the matter of that famous score.

The magic of Morricone: You can’t possibly write an analysis or appreciation of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly without referring to Ennio Morricone’s famous score. The Italian composer had previously collaborated with Leone on A Fistful of Dollars (credited as Dan Savio) and For a Few Dollars More, but this remains one of the most memorable of his prolific career (along with Once Upon a Time in the West, Once Upon a Time in America, The Mission and Cinema Paradiso). I mentioned The Trio piece above which is a perfect complement to the Sad Hill Cemetery Mexican standoff, but also consider such pieces as the poignant The Story of a Soldier which is sung by inmates at the Baterville POW camp whilst Tuco is being tortured; and also The Death of a Soldier. Morricone adopted a Brian Wilson/Pet Sounds innovative approach by integrating noises such as gunfire, whistling and yodeling into his compositions. The very familiar main theme itself resembles the howling of a coyote; with a leitmotif instrument used for each of the three principal characters. In so many ways the Morricone score was ahead of its time just as the film itself was. Quite deservedly, it still enjoys its reputation today as one of the greatest and most recognisable film scores of all time.

The 2004 Special Edition: A Special Edition of the film was made available on DVD in 2004 which re-inserts scenes originally deleted by distributors from the British and American theatrical versions. Eastwood and Wallach participated in this restoration by dubbing their characters’ lines. Van Cleef – who passed away in 1989 – was dubbed by voice actor Simon Prescott. For the purposes of this article, I watched this version again recently and found myself asking the question if any of the re-inserted scenes were of any great consequence or additional exposition. In truth, I think not. Yes, the scenes in question are interesting from an admirer’s point of view, but really the film stands up on its own without their presence. Tuco’s enlisting of the help of three fellow bandits to capture Blondie is one such, and I already mentioned the scene in which Angel Eyes passes through a Confederate outpost. The desert crossing scene involving Tuco and Blondie has been extended, but really it’s just more of the bandit torturing his former partner with the intention of killing him for severing their business arrangement. Elsewhere, there is a scene in which Blondie outs Angel Eyes’ henchmen who are shadowing them to Sad Hill Cemetery. But none of these, or the other restored scenes, are absolutely necessary to the narrative or the viewer’s understanding of it. So, if you haven’t seen this version, believe me when I say it’s no big deal. The theatrical version was just fine as it was. Whichever version you personally prefer, I hope you enjoy this film over and over as I do. Happy 50th The Good, the Bad and the Ugly!